The Black Market Trade for Endangered Animals Flourishes on the Web

On a May morning in 2008, a team of biologists doing some fieldwork in Borneo sat down to eat their lunch, only to notice a visitor in their midst. An odd lizard, partially concealed in some leaf litter, blinked back at them from a shallow creek bed. It had the worm-like body of a Chinese dragon and the face of a character from The Land Before Time. One person in the group picked up the lizard and the researchers snapped a few photos, but they soon lost interest, put the strange creature back where they found it and resumed their lunch. “No effort was made to collect the animal, in part because the scientific import of the discovery was not fully appreciated,” they later wrote. “As the team resumed their walk, one member looked back to view the lizard again, but it had disappeared.”

Only later did they realize they had found Lanthanotus borneensis, an extremely rare reptile some experts reverently refer to as “the holy grail of herpetology.” Also known as the Borneo earless monitor lizard, it most closely resembles an extinct 70-million-year-old species from Mongolia, and its morphology is special enough to warrant its own branch on the monitor lizard family tree. A nocturnal, secretive animal, it was first described in 1877, rediscovered in 1963 and had—until those researchers sat down to their lunch—virtually never been seen since.

The Borneo earless monitor, Lanthanotus borneensis, is pictured. Matthijs Kuijpers/Alamy

The Borneo earless monitor, Lanthanotus borneensis, is pictured. Matthijs Kuijpers/Alamy

Try Newsweek for only $1.25 per week

This discovery, the biologists knew, would be of interest not only to scientists but also to fervent collectors around the world. “It cannot be ruled out that pet reptile collectors and traders may misuse” geographical coordinates revealing the lizards’ whereabouts, the researchers wrote. “We have therefore retained [geographic information system] data.” Still, their paper contained a rough map and detailed information about the habitat where they found the animal. Within a year, earless monitor lizards were for sale online.

Trading Without Fear

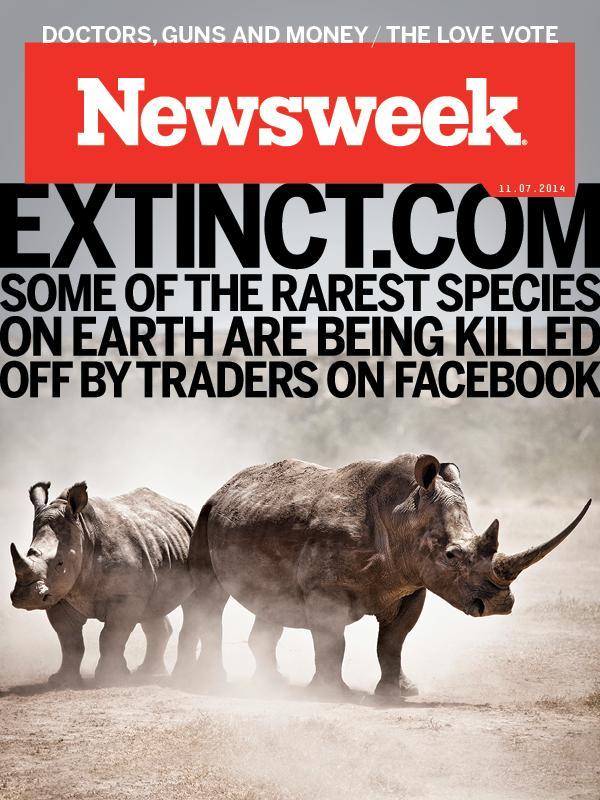

Just as the Internet has becomes the world’s largest marketplace for legal products, it also supports a flourishing network of criminal goods and services. From fueling demand for niche pets to connecting buyers with those offering anything from rhino horn tonics to highly endangered tortoises, the Internet allows the illegal wildlife trade to thrive as never before.

The trade is the fifth largest contraband trade, ranking just after narcotics. Excluding illegal trade in timber and fisheries, it nets an estimated $10 billion per year. All of those sales are taking a toll. According to a recent World Wildlife Fund study, 52 percent of wildlife populations around the world have disappeared since 1970, with overhunting being a major driver behind that decline. For some species, the study found, the illegal wildlife trade is now the primary threat, thanks to soaring demand for certain wildlife and animal-derived products. Elephants and rhinos are two stark examples of this. From 1998 to 2011, demand for ivory—which now fetches about $1,000 per pound—increased by 300 percent. In 2007, 13 rhinos were poached in South Africa; in 2011, that figure spiked to more than 1,000. Rhino horn, despite being the medicinal equivalent of eating fingernails or hair, now fetches its weight in gold—about $30,000 per pound. If that business continues as normal, rhinos will be extinct by 2020.

In this photograph taken on March 23, 2013, an Indian forest official walks past a dead rhino that was killed by poachers in Nagon. AFP/Getty

In this photograph taken on March 23, 2013, an Indian forest official walks past a dead rhino that was killed by poachers in Nagon. AFP/Getty

-

Shares: 15.3k

-

Shares: 14k

-

Shares: 7.5k

-

Shares: 2.5k

-

Shares: 514

- Most Read

Because of the covert nature of this trade, it’s impossible to know just how much of it is facilitated by the Internet. It is safe to say, however, that the majority of the trade has some online component, whether it’s connecting buyers to sellers, allowing traders to research the market for a new animal product or working out the logistics of a smuggling operation. “When we started investigating this, we began to expose this really dark underbelly of online markets,” says Crawford Allan, senior director of TRAFFIC, a wildlife trade monitoring network. “Some of the rarest species on Earth are being traded on Facebook.”

Some sellers are unaware that they are part of the illegal wildlife trade. Up to $13 million in ivory annually passes through LiveAuctioneers.com, but according to a recent investigation, almost none of the businesses selling the ivory can verify its provenance, meaning much of it is likely illegal. “The auction and antique world didn’t believe they were a problem, but these data show that they are playing a pretty substantial role,” says Anya Rushing, an assistant campaign officer at the International Fund for Animal Welfare (IFAW), the nonprofit that conducted the study.

Most involved in the online wildlife trade, however, are criminals who know they are breaking the law. But very few law enforcement organizations around the world have special divisions dedicated to wildlife, and until very recently, trade in animals wasn’t seen as a priority. “Law enforcement should really be doing this,” Allan says. But for the time being, “it’s largely up to organizations like ours to snoop around, validate the information we find, analyze it and then deliver it to authorities on a plate.”

Allan and like-minded conservationists tend to go after those at the top of the wildlife trade food chain rather than petty players who do on-the-ground grunt work. Analytical software allows agents to combine a variety of data—tips, online ads, email addresses, cell numbers, license plates and more—to form a larger picture of the networks and players involved. Once they think they’ve identified a ringleader, they present their data to authorities. Depending on where the criminal is based, that could be the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, the U.K.’s National Wildlife Crime Unit, Interpol or others.

There have been major victories. In 2012, data gathered by the IFAW in cooperation with the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service led to federal and state charges against more than 150 people selling everything from tiger skins to live birds. But on the whole, online traders know their chances of getting caught are relatively slim.

A Sumatran elephant walks near burnt trees at the Elephant Training Centre in Minas, Indonesia's Riau province in this February 29, 2008 file photo. Beawiharta/Reuters

A Sumatran elephant walks near burnt trees at the Elephant Training Centre in Minas, Indonesia's Riau province in this February 29, 2008 file photo. Beawiharta/Reuters

The dark Web—hidden portions of the Internet where users often operate in complete anonymity to sell guns, drugs and child pornography—is largely free of wildlife products, according to an investigation that Allan recently carried out with the help of a terrorism intelligence expert. That’s because those selling illegal wildlife products don’t find it necessary to retreat to the deep recesses of the Web. Due to lack of enforcement, they can carry out their activities either openly or by using simple code words—ox bone for elephant ivory, YTB for yellow-tailed black cockatoo, double engine or DE for red sand boas, four wheeler for star tortoise, striped T-shirt for tiger skin—to sneak their wares past search investigators and their algorithms.

Allan and others have worked with eBay, Google Shopping, Etsy and more to determine what animal products can and cannot be posted online. EBay has had some restrictions on wildlife—including a ban on live animals—in place for more than a decade, and it recently ramped those up to include ivory. In 2012, Google reached out to TRAFFIC for help in developing a set of policies for what animal products should and should not be allowed on Google Shopping; those rules were put in place six months later. In 2013, Etsy followed suit, banning products made from endangered wildlife and ivory. “Etsy had major issues for quite some time,” Allan says. “Oftentimes it’s a struggle for these online trading companies to understand the problem and to realize that it’s happening on their turf and that it’s an important issue. But Etsy eventually tuned in and responded.”

Websites in China—where the majority of illegal wildlife winds up—are also getting on board. In October, TRAFFIC solidified a new agreement to ramp up monitoring and anti-wildlife trade campaigns with Alibaba, the largest e-commerce company in the world. In the past, Alibaba’s listings have included things like new ivory and 1,000 bottles of tiger bone wine. “This is a big deal for us,” Allan says. “Alibaba is the online trading site of Asia—it’s massive.”

These efforts seem to be making a difference: The number of online Chinese ads listing tiger claws, teeth, bone and skin has significantly declined since 2012, according to a recent report. That doesn’t mean trade still isn’t an issue, however. “Just last week, I found some people selling ivory on eBay,” Allan says. The seller had listed it as an elephant carving broach—nowhere mentioning ivory—but Allan could tell by the material’s patterns that it was indeed made from newly carved elephant tusks.

“It’s like a whack-a-mole game,” says Wolfgang Weber, senior director of global regulatory and policy management at eBay. “We start blocking the term ox bone, and then sellers switch to another name like fauxivory.” For this reason, he says, it will never be possible to achieve 100 percent detection and prevention online.

My Pet Gharial Croc

When Vincent Nijman, a conservation ecologist at Oxford Brookes University, first spotted Facebook photos and videos of the earless monitor lizard in 2013, he immediately realized there was a problem. Online searching revealed that the lizards first went to Japan, and then made their way to Germany, Ukraine, the Czech Republic, France and the U.K. Because the species so recently appeared on the market, it’s guaranteed that all specimens have been taken from the wild—either Indonesia or Malaysia or possibly Brunei. Decades ago, all three countries created laws that strictly protect earless monitor lizards—poachers face a fine of up to $8,600 and five years’ imprisonment. “You can’t catch it, you can’t keep it, and you can’t buy it,” Nijman says. “And you certainly can’t take it with you out of the country.”

All that, however, was not enough to stop the lizard from being exploited for the pet trade. Nijman estimates that around 100 lizards have been illegally smuggled out of the wild so far.

A tiger is pictured in Bandhavgarh National Park in Madhya Pradesh, India. Art Wolfe/Gallery Stock Rare animals like the earless monitor lizard tend to appeal only to a subculture of the people who collect exotic animals. Like drug users, those collectors tend to have a substance of choice: lizards, turtles, birds or mammals. Allan says, “For many of them, it’s almost a pathological obsession with collecting the world’s rarest animals.”

A tiger is pictured in Bandhavgarh National Park in Madhya Pradesh, India. Art Wolfe/Gallery Stock Rare animals like the earless monitor lizard tend to appeal only to a subculture of the people who collect exotic animals. Like drug users, those collectors tend to have a substance of choice: lizards, turtles, birds or mammals. Allan says, “For many of them, it’s almost a pathological obsession with collecting the world’s rarest animals.”

In the past, yearly conferences tended to be the only place for collectors to meet other enthusiasts, but Facebook, YouTube, forums and chat rooms support a flourishing online community of collectors who can now place orders for live animals before they are even collected from the field.

Although no one knows how many earless monitor lizards exist in the wild, chances are, the species is not doing well. In recent years, forest fires and deforestation for agriculture and plantations have decimated much of the reptile’s estimated range. Add to that the pressure from collectors eager to turn a quick profit and it could be enough to push wild earless monitor lizards toward extinction.

This same scenario has played out before, with disastrous results. When news broke several years ago that researchers had discovered a population of red-and-blue lories, a type of rare parrot living on a small Indonesian island, suddenly every specialty bird collector on the planet had to have one. “There was a massive run for them, which virtually wiped them out in the wild, nearly overnight,” Allan says.

Likewise, the Kaiser’s spotted newt—a brightly colored amphibian whose facial features seem to be molded into a permanent smile—continues to be threatened with extinction. Around five years ago, news broke of its whereabouts in Iran, and pet traders have been smuggling it out of the country via Azerbaijan ever since. Experts estimate that fewer than 1,000 of the animals survive in the wild.

To sidestep the awkward fact that they are contributing to the extinction of the animals they purport to love, pet traders often claim that wild-caught animals are actually captive-bred. This helps them evade the law and also appeases buyers, who usually take the trader at his word. “There’s now a massive industry of bogus captive breeding,” Nijman says. The earless monitor lizard’s certain status as coming from the wild, however, makes it a uniquely clear-cut example of the pet-smuggling problem. As such, Nijman and a co-author quickly published a report detailing what they know about the trade, before collectors manage to breed the animals in captivity and complicate the playing field.

Since that document came out, Nijman has noticed that some of the videos and ads for earless monitor lizards have come down. Indeed, the BION Terrarium Center in Kiev, Ukraine, was implicated in Nijman’s investigation, but when a reporter asked about a YouTube video the center posted showing two earless monitor lizards, owner Dmitri Tkachev said that the video had been shot by the center’s “partner” and that BION is not working with those animals. Likewise, a gecko breeder from California who posted several enthusiastic photos and videos of an encounter with some earless monitor lizards in Japan declined to comment about that, and queries about an online ad for “longtime captive” earless monitor lizards, listed at €10,000 each by a seller in Germany, went unanswered.

But at least one reptile lover, Tsuyoshi Shirawa, owner of iZoo in Shizuoka and former head of one of Japan’s biggest reptile wholesale companies, is not shy about his involvement with earless monitor lizards. He purchased his first pair in April 2013, and his collection has since grown to seven, including several imported from Germany and Austria. Shirawa has become a sort of hub for information about captive earless monitor lizards. “Many people are looking for that lizard,” he says.

Shirawa has his sights set on becoming the first person to successfully breed the animals, but he vehemently insists that he does not plan to sell any of them. Instead, he wants to give the lizards to scientists. Researchers from Tokyo University, Shizuoka University, Nagoya City University, the National Museum of Natural History in Paris and others have either visited or contacted him for information about his earless monitor lizards, he says, and he has even given out some DNA samples. (Allan points out that some scientists can be just as starry-eyed as collectors—“Sometimes academics don’t ask enough questions about the origins of specimens”—or, more worryingly, “think that they don’t need to follow the rules.”)

Shirawa, however, says he’s happy to collaborate with anyone who approaches him for valid research purposes. “I want to give everybody my data,” he says. “Conservation of this animal is very much needed, but if we don’t know anything about it, we won’t know how to keep it.”

Allan, however, cries foul at this line of reasoning. “I’ve met many of these people myself, and some of them actually convince themselves that they’re conservation heroes,” he says. “They decide that the ends justify the means—that they smuggled wildlife with the best of intentions, and therefore should be treated with respect and applause rather than being jailed.”

Seized ivory tusks, rhino horn and leopard skins, with a street value of around four million Euro, are seen at the Hong Kong Customs and Excise headquarters in Hong Kong, China, 07 August 2013. This large seizure of wildlife products bound from Nigeria was disguised as timber inside two containers. Alex Hofford/EPA Often, however, animals bred in someone’s basement or closet suffer from genetic bottlenecking and risk transmitting exotic diseases to native populations should they ever be reintroduced into the wild. “The captive breeding community feel they’re doing a service,” Allan says. “But really, they’re only doing a service to themselves, for their own collection and their back pocket.”

Seized ivory tusks, rhino horn and leopard skins, with a street value of around four million Euro, are seen at the Hong Kong Customs and Excise headquarters in Hong Kong, China, 07 August 2013. This large seizure of wildlife products bound from Nigeria was disguised as timber inside two containers. Alex Hofford/EPA Often, however, animals bred in someone’s basement or closet suffer from genetic bottlenecking and risk transmitting exotic diseases to native populations should they ever be reintroduced into the wild. “The captive breeding community feel they’re doing a service,” Allan says. “But really, they’re only doing a service to themselves, for their own collection and their back pocket.”

When Shirawa, now 45, was 20 years old, he was caught trying to smuggle nearly 300 endangered turtles and lizards into Japan from Southeast Asia. Then, in 2007, he was sentenced to more than two years in jail and fined $15,330 for claiming that wild-caught radiated tortoises and false gharial crocodiles in his possession had been captive-bred in Japan. “I understand that what I did in the past was very bad, and I’m very ashamed of it and have apologized,” he says. “I’ve changed now: I don’t break the law. I just really love reptiles and always want to be together with them.”

His activities with the earless monitor lizards are “not illegal trafficking,” he continues, and he registered all of his specimens with local authorities in Japan. “I asked my government and they said it’s no problem to import it, because this is a non-CITES species,” he says, referring to the Convention on the International Trade in Endangered Species—an agreement among 180 countries about what animals can and cannot be traded internationally.

Nijman points out, however, that the intentions of Indonesia, Malaysia and Brunei are clear: Trade is not allowed. “We have to respect that,” he says.

If Shirawa’s story is true, then Japan, at least, is not respecting that intention—or perhaps is simply not aware of those laws. To clear up any confusion, ignorance or laziness on the part of customs officials, Nijman is pushing for CITES to add the earless monitor lizard to its highest-priority protection list so there will be no question about whether the trade is legal.

No doubt, however, it will only be a matter of time before the earless monitor lizard gets a code name for evading authorities, and the investigation will have to begin anew.

“It’s an arms race,” Allan says. “It will continue this way until either wildlife goes extinct or there’s a sea change in demand, where people are no longer willing to buy this stuff.”