The gana-sangha, or gana-rajya, was a distinctive form of governance in ancient India, contrasting sharply with the traditional kingdoms. Primarily located in the hilly and less fertile regions of the Indo-Gangetic Plain, especially in north-western India, including areas like Punjab, Sind, and parts of central and western India, these assemblies showcased a unique societal structure.

The essence of the term gana means “equal,” while sangha signifies “assembly” or “governance.” In this system, governance was often in the hands of clan heads, who operated within an assembly framework limited to their clan members. Although some scholars have likened this system to democracy, it functioned more as an oligarchy, where power resided with a few ruling families, leaving the majority of the population with minimal rights and resources. Thus, the gana-sanghas can be viewed as pre-states or proto-states that diverged from monarchical traditions.

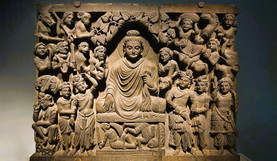

Notably, the gana-sanghas comprised either single clans, such as the Shakyas, Koliyas, and Mallas, or a confederacy of clans like the Vrijjis and Vrishnis. Despite the formation of confederacies, each clan maintained its autonomy. The Vrijji clan, identified as a Kshatriya clan, notably rejected the orthodox varna system, indicating a more egalitarian social structure.

Societally, the gana-sanghas were structured into two main strata: the kshatriya rajakula (ruling families) and the dasa-karmakara (slaves and laborers). Their rejection of Vedic rituals in favor of alternative religious practices exemplifies their divergence from mainstream traditions, highlighting a culture that embraced varied religious expressions.

In summary, the gana-sanghas represented an alternative governance model in ancient India, fostering egalitarian ideals among ruling clans while firmly establishing their unique identity within the historical narrative of Indian polity.