Manchester United takeover: Sheikh Jassim, Qatar and just enough separation

229

Separation (noun): the act of separating people or things; the state of being separate.

Ten letters, four syllables and dozens of different interpretations of what it means when it comes to football.

Manchester United fans are going to hear and read a lot about these interpretations in the coming weeks, and the debate is going to be loud, impassioned and partisan. But it will also be irrelevant.

Because one of the bidders for United, Sir Jim Ratcliffe, is not even trying to prove separation between the English club and the ones he already owns in France and Switzerland. And the other, Qatar’s Sheikh Jassim bin Hamad Al Thani, has gone to some effort to give an impression of separation.

Will either of those two positions — one very obviously not separate, the other obviously trying to look separate — matter? No, not really. Football lost the separation argument years ago.

European football’s governing body UEFA just about resisted the first challenge to the basic principle that no single person or entity should control two or more teams in the same competition when it stood up to ENIC in the late 1990s. The British investment group was a multi-club pioneer and had a stable of teams across Europe. Three made the quarter-finals of Cup Winners’ Cup in the 1997-98 season and two of them — AEK Athens and Slavia Prague — qualified for the UEFA Cup the following campaign.

UEFA introduced a rule that meant only one of them could take part in the competition. ENIC appealed and gained an injunction that meant both AEK and Slavia could play but, in 1999, the Court of Arbitration for Sport backed UEFA’s rule, effectively ending ENIC’s multi-club experiment. It decided to put all its eggs in the Tottenham Hotspur basket instead, which is where they have remained.

UEFA’s rule did not, however, kill the multi-club idea and, in 2017, it blinked when Austrian soft drinks giant Red Bull’s two main footballing ventures, RB Leipzig and Red Bull Salzburg, qualified for the Champions League.

After some Chinese walls were erected, parent-company executives removed and staff ring-fenced, Leipzig were allowed to join their sister club on football’s brightest stage. Given the huge growth in the number of clubs that share owners or co-owners, it was only a matter of time before somebody took a run at the regulations and it did not require much effort for Red Bull to smash through.

RB Leipzig and Red Bull Salzburg meet in the Europa League in September 2018 (Photo: Matthias Kern/Bongarts/Getty Images)

Over the last 10 years, the total of European clubs with sister clubs has grown fivefold. There are now at least 180 clubs worldwide that are part of multi-club groups and 82 of them are in Europe’s top divisions.

In its most recent report on European football’s financial landscape, UEFA noted that “the rise of multi-club investment has the potential to pose a material threat to the integrity of European club competitions, with a growing risk of seeing two clubs with the same owner or investor facing each other on the pitch”.

Great point, lads, but you’re too late.

Which brings us back to Manchester United’s suitors: Ratcliffe, who already owns Lausanne-Sport and OGC Nice, and Sheikh Jassim, who does not own any other clubs but knows a man who does.

We have already written several pieces about Ratcliffe, as his interest in buying a Premier League club is not new, but Sheikh Jassim is a new name to everyone outside Qatari banking circles.

So this is about his tango with UEFA’s rules and why they are very unlikely to stop him from dancing away with the prize, if his bid for United is accepted.

The Athletic’s coverage of the Man United takeover…

- Sir Jim Ratcliffe’s Man United bid – key questions answered

- ‘It is not wrong to question Qatar’s bid – and we will’

- Sheikh Jassim’s bid, the Qatar issue and what it means for Ratcliffe

On the face of it, why should it matter if he knows a man who owns a club? Ratcliffe must know a few other owners, too, and it does not mean he has any further “control” complications to navigate than the obvious one in Nice.

But when the man in question is the Emir of Qatar, and you are a member of his ruling tribe, knowing him brings more pressure than having to provide a decent pre-match meal or be polite at meetings. And the emir, Sheikh Tamim bin Hamad Al Thani, is the ultimate owner of Paris Saint-Germain, France’s best team and very possible future opponent of Manchester United.

“There are approximately 3,000 members of the Qatari royal family and only a small proportion of them are close to the emir and his inner circle, which means most family members have little power or influence over government policy,” explains Professor Simon Chadwick, an expert on sport and geopolitical economy at the SKEMA Business School.

“This is where Sheikh Jassim comes in: he is sufficiently far away enough from the centre of power and therefore serves a purpose in terms of distancing the Manchester United deal from PSG (who are owned by a state-backed fund called Qatar Sports Investments).

“Nevertheless, it’s important to note that in Gulf culture, familial ties run deep. When a member of the extended network is called to action, the expectation is they will oblige. Such an obligation is, in general, willingly fulfilled as it provides an opportunity to ascend the hierarchy of power, which owning United would enable.

“And with such an ascent comes more status, more influence and, potentially, more power. Irrespective of who or what might present itself as the face of Qatar at Manchester United, nobody should be under any illusions about the omnipotent power of the Qatari government, or that family and country come first, not self-interest.”

Last week, human rights group FairSquare wrote to UEFA president Aleksander Ceferin, copying in Premier League boss Richard Masters, to point out that any Qatari bid for United would be linked to Qatar’s existing ownership of PSG, which should rule it out.

“A basic study of Qatar’s political and economic system amply demonstrates the impossibility of any Qatari consortium proving itself independent of state influence, and thus separate from the ownership of PSG,” wrote FairSquare.

“UEFA’s statutes are clear on the critical importance of ensuring that no single party can exercise control or influence over more than one club, and this is all the more important when the owners are states.”

Great point, lads, but you’re too late.

Born in 1982, Sheikh Jassim is described as a lifelong Manchester United fan. He became chairman of Qatar Islamic Bank (QIB) in his early twenties, shortly after graduating as an officer cadet from the UK’s Royal Military Academy at Sandhurst. He has also been a director at Credit Suisse Group, as well as serving on the boards of other Qatari companies.

His bid for United will come from a not-for-profit entity he is setting up called the Nine Two Foundation — 1992 being the year he apparently started following the club and a nod to the “Class of ’92” crop of players that emerged from United’s academy that year to dominate English football for the next decade or so.

The PR people he has appointed are not saying how much he has bid for the club but the consensus is that it is in the region of £4.5billion ($5.4bn) and he can go higher if need be. He is proposing to buy out the majority owners, the Glazer family, as well as the publicly-listed company’s minority shareholders.

He will do this with cash, clearing the club’s debts, and he will then spend whatever it takes to return United to the top of European football, rebuilding the stadium and training ground in the process, as well as investing in the wider area in a similar fashion to Manchester City’s Abu Dhabi-backed owners in east Manchester. Sheikh Jassim will not forget the women’s team, either. It is a popular bid.

So, how is this 40-something chairman of a mid-sized bank — by global standards — affording all that?

His father is Sheikh Hamad bin Jassim bin Jaber Al Thani, who you can tell is a major player because he is known by his initials, HBJ.

Foreign secretary between 1992 and 2013, HBJ also served as prime minister between 2007 and 2013, and managed to find time to be the deputy head of Qatar’s sovereign wealth fund, the Qatar Investment Authority (QIA).

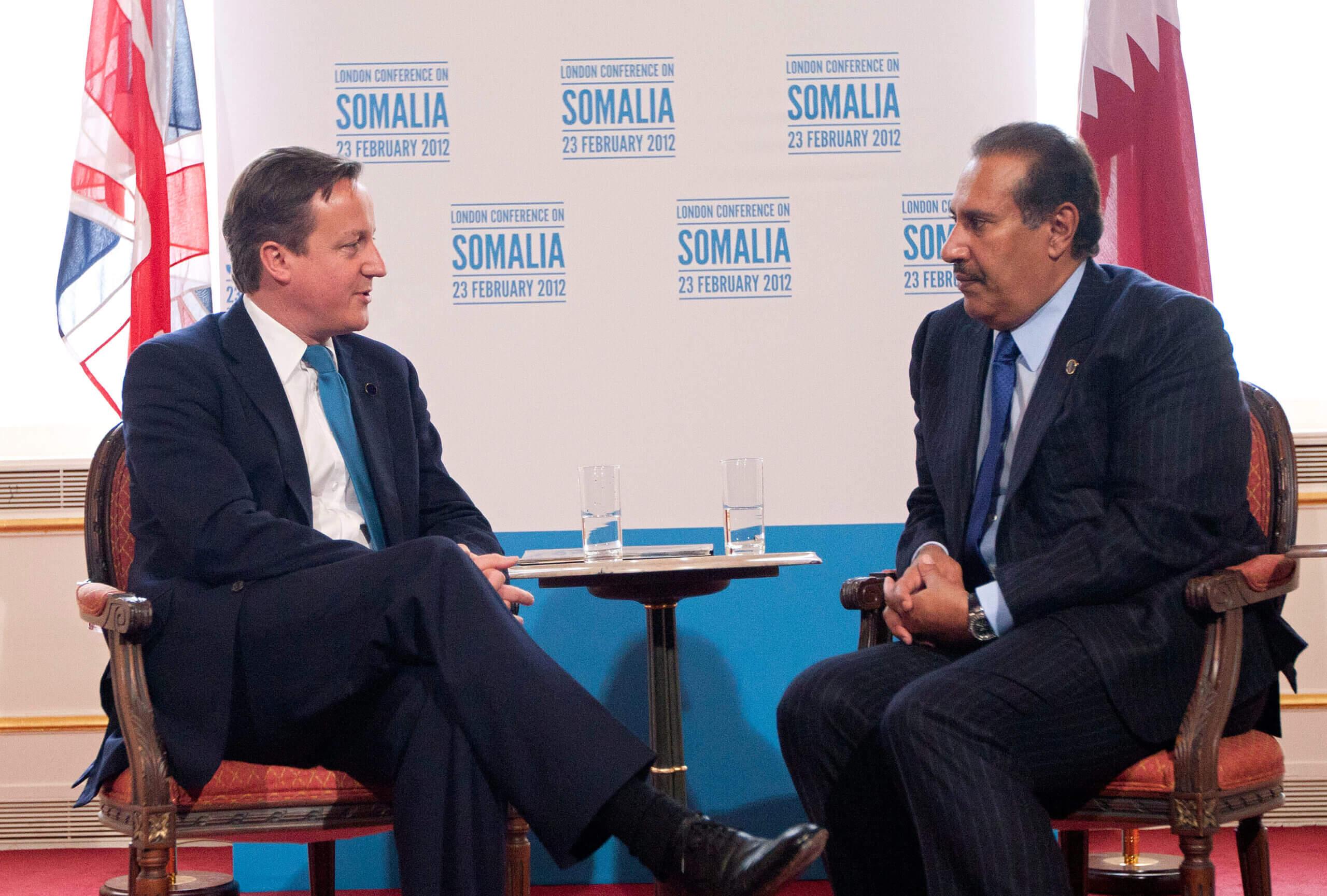

The UK’s then-prime David Cameron meets with Sheikh Hamad in London in February 2012 (Photo: Matt Dunham/AFP via Getty Images)

“He was the former emir’s right-hand man — they were a double act — and the emir used to joke that while he ran Qatar, HBJ owned it,” explains David Harding, Agence France-Presse’s former bureau chief in Doha.

“He was also known as the man who bought London, as it was on his watch that Qatar started buying up trophy assets such as Canary Wharf, Harrods, (London’s) Olympic Village and the Shard.”

But that emir, Sheikh Hamad bin Khalifa Al Thani, abdicated in 2013 and was succeeded by his fourth son, the previously mentioned Sheikh Tamim, who is perhaps best known internationally for putting a ceremonial robe over Lionel Messi’s shoulders after Argentina’s World Cup win in December.

Sheikh Tamim’s arrival signalled HBJ’s exit. He resigned from his government posts the following day and lost his QIA job a week later.

Why? Well, the emir does not need to explain himself but seasoned Qatar watchers believe it was a combination of HBJ simply being so rich and well-connected that he posed a potential threat to the new boss, and the fact that HBJ had made a few enemies along the way thanks to his free-wheeling approach to foreign policy. For instance, it is widely believed that he — perhaps inadvertently — funded rebels linked to Al-Qaeda during the civil war in Syria.

“HBJ was replaced when the emir stood down as part of a changing of the guard designed to give Sheikh Tamim the space to chart his own path as leader,” says Dr Kristian Ulrichsen, an expert on Gulf politics at Rice University’s Baker Institute for Public Policy.

So, HBJ stepped away and was rarely seen in Qatar for the next few years, although he remained close to Sheikh Hamad, who is now known as the Father Emir, and continued to make business news internationally. In fact, one of the most significant Qatar-related stories of the last decade has been the gradual realisation of just how rich HBJ had become.

For example, in 2014, Qatar’s sovereign wealth fund took control of Qatar Airways, buying out the stakes owned by HBJ and other members of the elite. At the time, it was not public knowledge HBJ had taken a personal stake in the country’s flag carrier but he actually owned almost half of the company.

Speaking to the Reuters news agency, a government was reported as saying: “Changes are happening — Qatar wants to have a fair and competitive business environment for everyone.”

HBJ’s name has also cropped up in several business disputes that ended up in the London courts, one of which involved an allegation of kidnapping and torture made by a British national against agents acting on HBJ’s behalf. However, the case was thrown out before it really got started as HBJ was able to claim diplomatic immunity.

HBJ’s lawyers welcomed the ruling as a vindication of their client and there is no suggestion he broke the law in this case or in any of the other cases in which he, or Qatar, became entangled. But the overriding impression is HBJ is basically the point at which Qatar’s growing international power met the private ambitions of its elite.

“Few countries fit the description of state capitalism better than Qatar, and few fit the role of a state capitalist better than Prime Minister and Minister of Foreign Affairs Sheikh Hamad, through his multiple roles as politician-cum-businessman,” wrote Norwegian diplomat Anders Gulbrandsen in 2010.

Noting the various hats HBJ wore at the time, the diplomat explained that the arch-networker routinely invested his own money in the same investments he was making on behalf of the state. One example was Qatar’s bailout of Barclays Bank after the 2008 economic crisis, which left the British bank challenging a provisional fine of £50million for failing to disclose the deal. It was an amazing investment for Qatar and HBJ, though.

But Gulbrandsen’s thesis is also the earliest published mention of his eldest son Sheikh Jassim, as it notes that HBJ’s business empire has a “heavy reliance” on close allies and family members. Sheikh Jassim sits on various boards on his behalf, most notably QIB, whose largest shareholder was QIA, the sovereign wealth fund HBJ directed for so long. There is also a delicious line about HBJ having personal stakes in half of the companies listed on Qatar’s stock exchange.

Lionel Messi is presented with a traditional robe by Sheikh Tamim, emir of Qatar, at the World Cup final (Photo: Clive Brunskill/Getty Images)

“The dividing line between state money and private money in Qatar is so very thin,” says Harding. “I cannot see how this bid for United has not been sanctioned by the very top — I can’t see how it’s anything other than a state bid.”

Harding also notes that the Premier League is a more natural fit for Qatar, a former British protectorate with a penchant for buying “the best”, than Ligue 1, while it is also believed that the current emir is a Manchester United fan.

As anyone who followed our coverage of the World Cup will know, there are several reasons Qatari ownership of one of Britain’s most popular institutions would be problematic. This piece is focused on a different aspect of the debate but if you need a recap on the general controversies, this article is a good starting point.

The Athletic has also spoken to several people who still work in senior positions in Qatar. Getting them to go on the record, when their livelihoods depend on discretion, is almost impossible but one source with a decade of experience in the country put it like this: “It’s classic Qatari shenanigans — Sheikh Jassim is a bit of a nonentity. They needed a private individual who won’t be an issue for UEFA’s rules.

“Has Sheikh Jassim earned $5billion in his career? Probably not but his father is the key figure in this. Who knows what his net worth really is — it would be pure speculation (for what it is worth, the 2022 Sunday Times Rich List had it at just over £2billion, a number many believe is very, very conservative).

“The most contentious question in any Gulf state is where does state money end and private money start? A government budget is published every year but that’s just what the government spends — it’s only a small percentage of the total income from oil and gas.

“Qatar has obviously done very well from high energy prices. All that money has come in but where does it go? That’s the politically contentious question.”

Sheikh Jassim’s spokespeople are not speaking on the record, either, but they have privately stressed his bid is not connected to the state, the sovereign wealth fund or PSG. They say it is his money, in his foundation, and he wants to spend it on his club.

And The Athletic has spoken to one Gulf expert who agrees.

“I wouldn’t necessarily see this as a ‘Qatari’ bid,” says Gerd Nonneman, a professor of international relations and Gulf studies at Georgetown University in Qatar.

“Sheikh Jassim doesn’t hold any government positions, nor, indeed, has his father done for many years. Much of the son’s fortune is based on his father’s wealth, which is thought to run into the billions, further enhanced by his own involvement in QIB and other business ventures.

“So, contrary to the investments in Bayern Munich (a Qatar Airways sponsorship deal) or PSG, which were done by entities that were largely funded by the state and/or very senior members of the ruling family, this case is different.

“Of course, we don’t know who else, apart from HBJ, might have a stake in Sheikh Jassim’s Nine Two investment vehicle, but there doesn’t seem to be any controlling stake by any government entity of any of the actual ruling group.”

As far as anyone can tell at the moment, this is true. But as several others have explained to The Athletic, the use of foundations to fund socio-cultural causes or projects that promote the country or ruling family are common among the Qatari elite.

“And it is important to stress, again, that family and country come first, before any one individual or clique,” notes Professor Chadwick.

So, we have a bid led by the son of a man who has made his family rich enough to buy Manchester United with his own cash but who, 10 years ago, was too privately wealthy for comfort in Qatar. That made him a potential threat to the new emir. But now the son’s private wealth is required.

In many ways, it is the perfect bid for our cynical times and the governance challenges it poses for UEFA and the Premier League are what those institutions deserve for not holding the line many years ago.

As another source who still works for Qatar, and cannot speak on the record, puts it: “Co-ownership and multi-clubs have polluted European football. Who knows who owns what clubs these days?

“Red Bull, the nonsense over (the Public Investment Fund) and Newcastle United, it’s all been signed off. It’s everywhere and Qatar is the last to the party.”

(Top photos, left to right: HBJ, Sheikh Tamim with Messi, Sheikh Jassim. Getty