What if the Premier League had spending caps for clubs like La Liga?

The Premier League is one of the UK’s most successful exports and everyone in it makes money, right? Well, the first part of that statement is true, with the broadcast rights the envy of the rest of the football world and only fans in five countries (North Korea, Cuba, Afghanistan, Moldova and Turkmenistan) are denied the chance to watch Norwich vs Burnley on a Monday night.

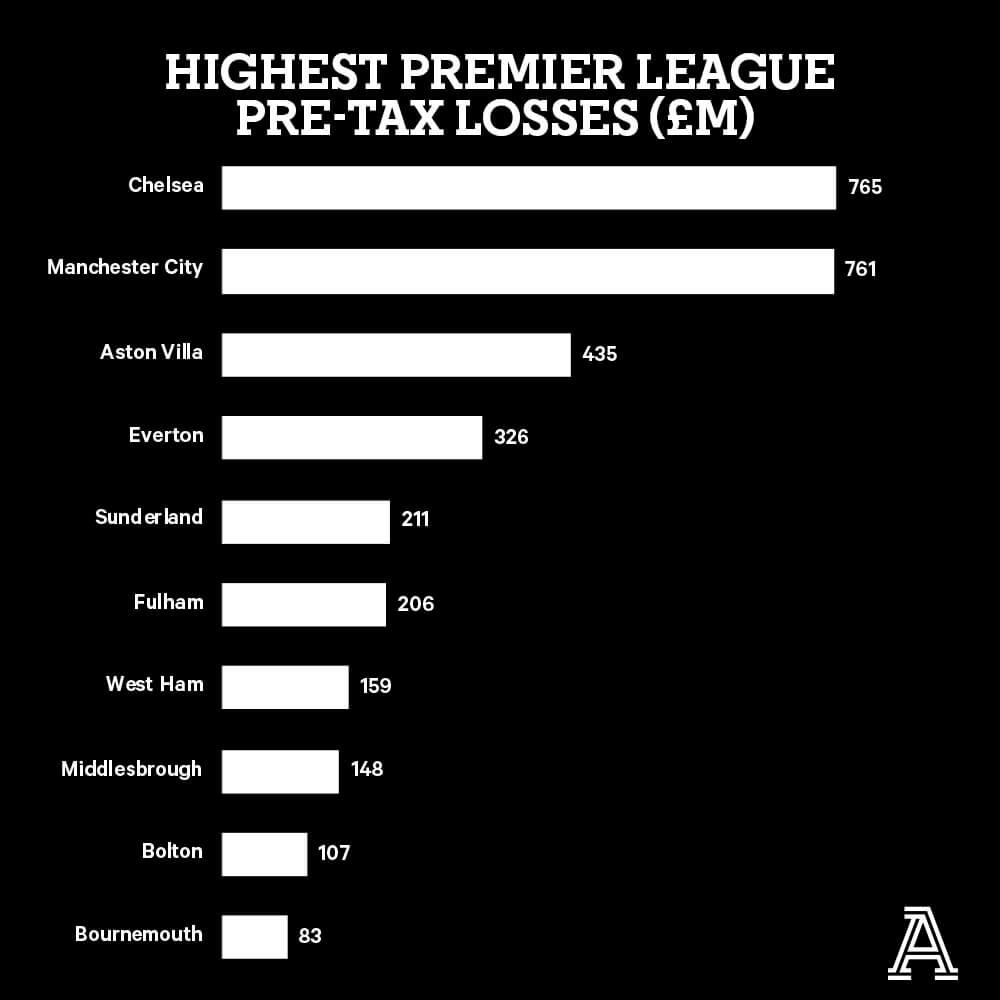

When it comes to making money, the jury is out, at best. When Chelsea played Manchester City in the Champions League final in May, the match featured the two clubs that had made the highest pre-tax losses in Premier League history. Between them, Chelsea and City had lost over £1.5 billion, a price worth paying if you look in the trophy cabinet. But, according to some, such spending reduces the sustainability of the domestic game as others play catch-up in terms of wages and transfer fees.

The present “Profitability and Sustainability” rules (a name probably devised by Premier League middle management on a blue-sky thinking awayday in a hotel conference room), which most fans still refer to as financial fair play, is a “breakeven” model. Clubs are allowed to lose £15 million pre-tax over a rolling three-year period. However, certain costs (academy, community, women’s team, infrastructure) are excluded, and owners are allowed to contribute via share issues a further £90 million over the three-year period.

These rules have some merit, but one of the flaws is that they are based on historic published financial accounts, which are not published until well after the end of the season (or in the case of Newcastle and Crystal Palace for 2019-20, after the end of the following season, as neither club have, as yet, sent in their accounts to Companies House).

This means that if the Premier League does apply any sanctions, they are always after the event — trophies, Champions League places and relegation will have been determined already. Bournemouth and Leicester were both promoted to the Premier League from the EFL and subsequently came to financial settlements for breaches of rules while in the Championship.

The alternative to a breakeven model is some form of spending cap. A hard cap is where there is a total wage limit that is the same for each club. This operates in American franchise sports such as MLS, the NBA and the NFL and, along with the draft system, helps to spread the success around. This prevents one or a small group of teams from dominating the sport.

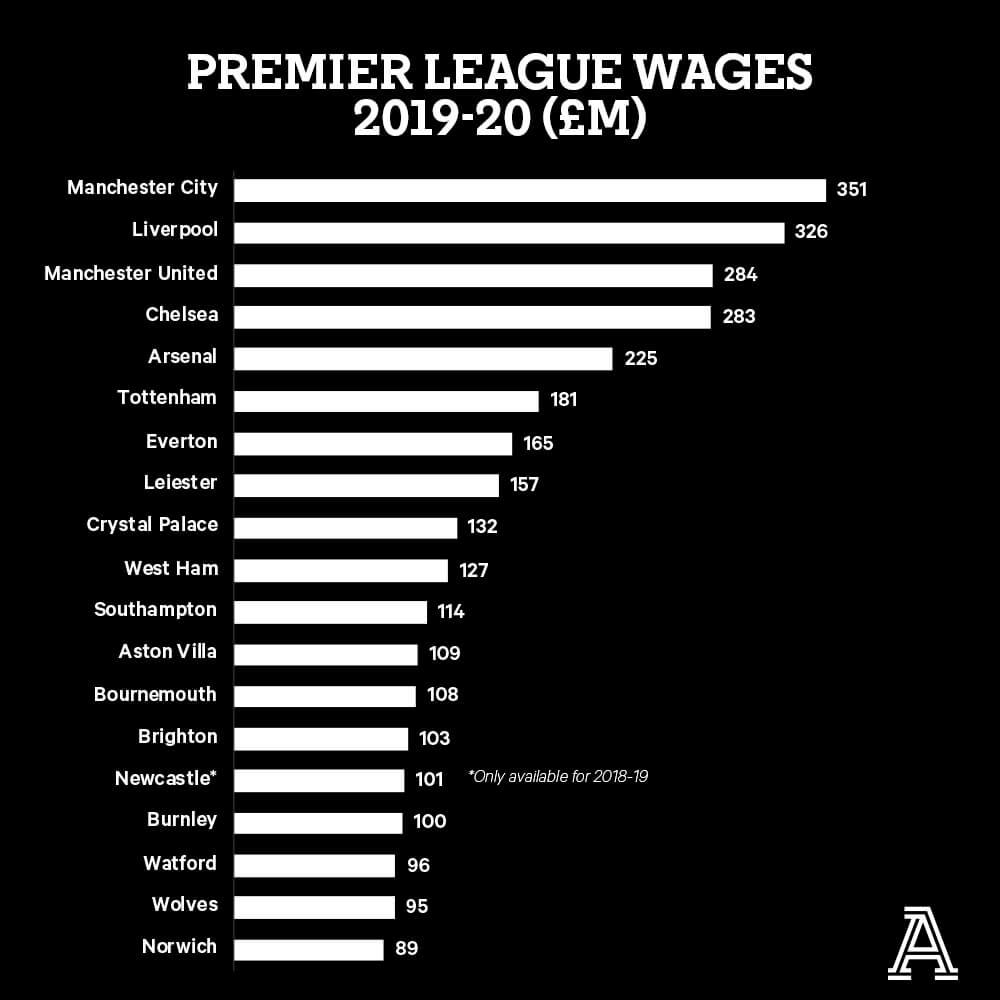

There is no appetite for this in the Premier League and the range of the wage table is more than £250 million. This is partly due to the business models of some owners, whose focus is on trophies, and also due to the Premier League elite seeing their competitors as the other big clubs in Europe rather than small but reasonably established Premier League clubs such as Burnley and Crystal Palace.

A cap set at, say, 20 per cent over the average Premier League wage bill would give a figure of £193 million, which would only affect five clubs. These clubs might legitimately claim that they were being held back on the European stage by such a policy and could easily afford to pay more. This could be through their commercial income on the back of being global brands (Liverpool and Manchester United), or owner investments (Chelsea and Manchester City).

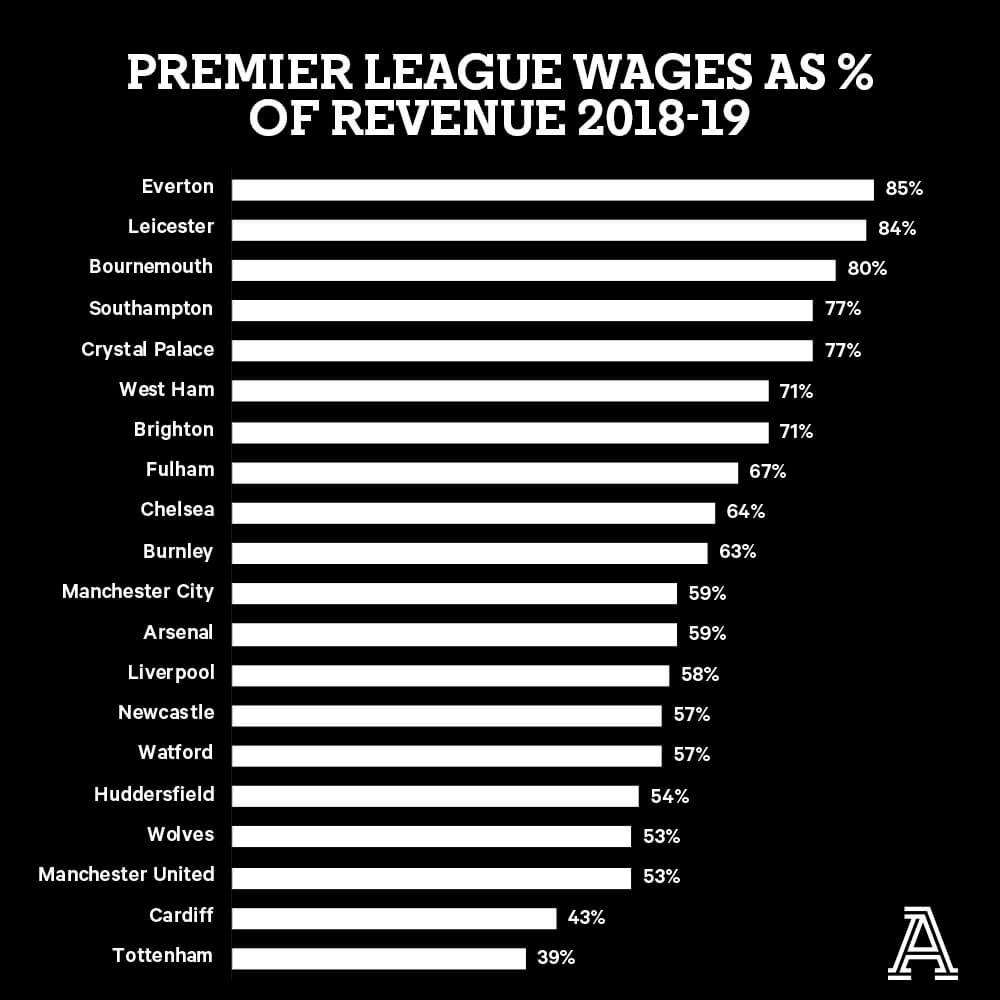

The alternative to a hard cap is a soft one, where wages are linked to revenues. UEFA often talks of a “red line” of keeping wages to no more than 70 per cent of revenue. The Premier League’s revenues were distorted in 2019-20 so a look at the figures for the season before shows that seven clubs in 2018-19 were over the line, none of whom would have been impacted by the hard-cap limit. Tottenham, in particular, have had very effective control over their employment cost, although whether this will prompt their fans to chant “Wage control champions, you’ll never sing that” to clubs struggling in that particular area — such as Leicester and Everton — when they come to the new stadium is uncertain.

However, wage caps ignore the impact of transfer fees on clubs. Players signed on Bosman deals are usually able to command higher wages as clubs look at the total cost of recruiting a player, which is both wages and amortisation (transfer fee spread over contract life). Therefore, there is a case for taking transfer costs into consideration too.

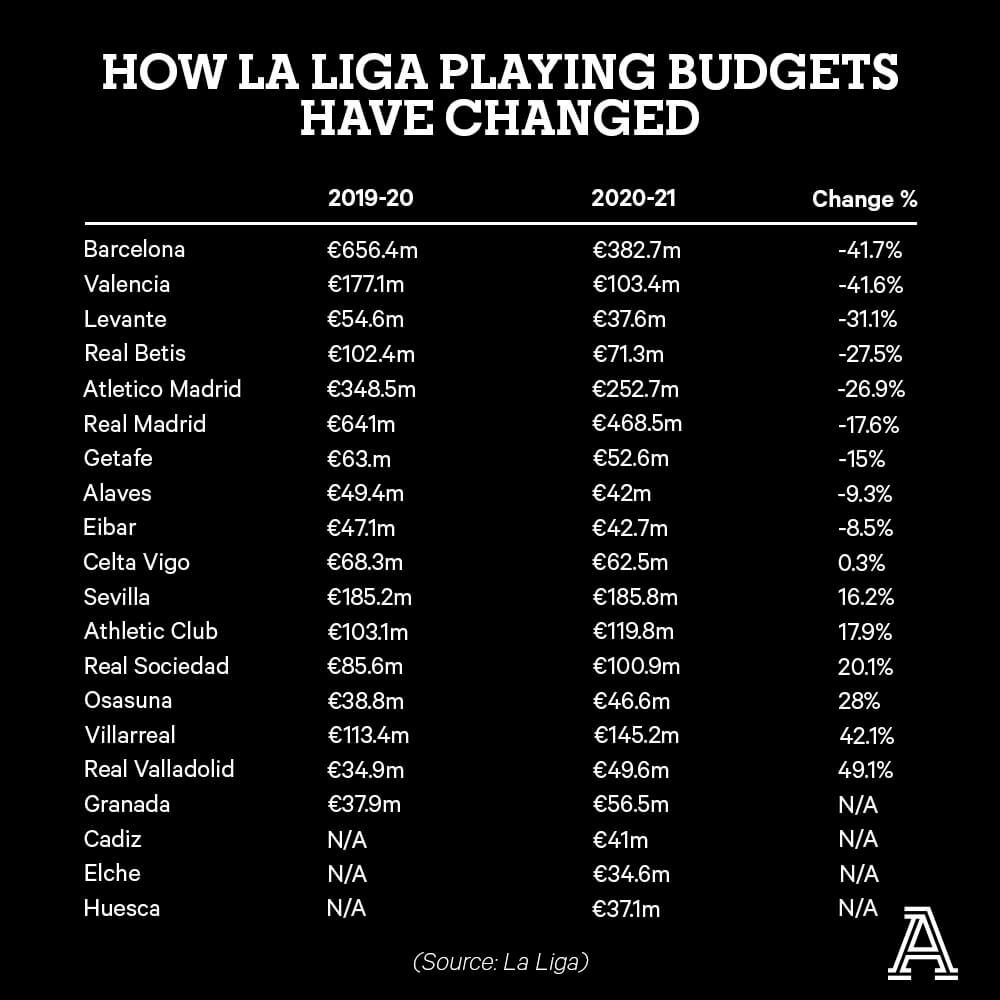

In La Liga, the “Economic Cost Control” measures that operate there are forward based, rather than assessing clubs on their past financial results. The approach taken is aimed at preventing clubs from overspending and the resulting unsustainable debt.

Clubs have to submit estimated figures for both their revenue (including player sales) and costs, including player purchases. La Liga’s team of spreadsheet experts then analyse the estimates for reasonableness, looking at transfer values in the present market for example. On the back of these submitted figures, La Liga then gives the clubs a total sum that they can spend during the following season, but allows the clubs to allocate this between transfers and wages (including the academy, first-team coaches and physios) as they see fit.

La Liga’s rulebook covers 261 pages and the formula used to determine the actual budget given to clubs is, a bit like Kentucky Fried Chicken’s blend of herbs and spices, a closely-guarded secret. Each La Liga club is then assessed on its recent cost control over the last three years and this is compared to the budget. The main elements of the formula used by La Liga’s analysts involve four financial metrics:

Economic profitability (economic performance and efficiency)

- Ordinary profit before tax divided by total assets

Financial profitability (profit generated by the partners and owners)

- Ordinary profit before tax divided by equity

General liquidity

- Current assets divided by liquid liabilities

Solvency

- Equity divided by total assets

Where La Liga rules show their teeth is that clubs have to register their players using an app as they are signed. If the wages and transfer fee result in the club exceeding the allowed limit, the app flashes red. This means the club either have to reduce wages with existing squad members and/or sell a player so that the new recruit can be registered to play for the forthcoming season. Barcelona’s problems for 2021-22 are well documented.

The effect of this on the back of COVID-19 was to hit clubs who had been overspending hard, but if it helps ensure long-term survival then it could be deemed to be a financial challenge worth undertaking.

Would this work in the Premier League? The first thing that would be required for a vote to take place and a two-thirds majority (14 clubs) to vote in favour of a change to the existing rules. Whether clubs with ultra-high net worth owners such as Chelsea, Manchester City, Aston Villa, Everton — and potentially Newcastle United if Mike Ashley is successful in selling the club to Saudi Arabia’s Public Investment Fund — would be keen to have such controls is uncertain. Clubs in La Liga are often member-owned and this means they are not in a position to ask their owners to bail them out as has been the case with many Premier League clubs.

If an independent football regulator, one of the recommendations of the interim fan-led review report produced by Tracey Crouch MP, is introduced, then this issue may be taken out of their hands and could be imposed.

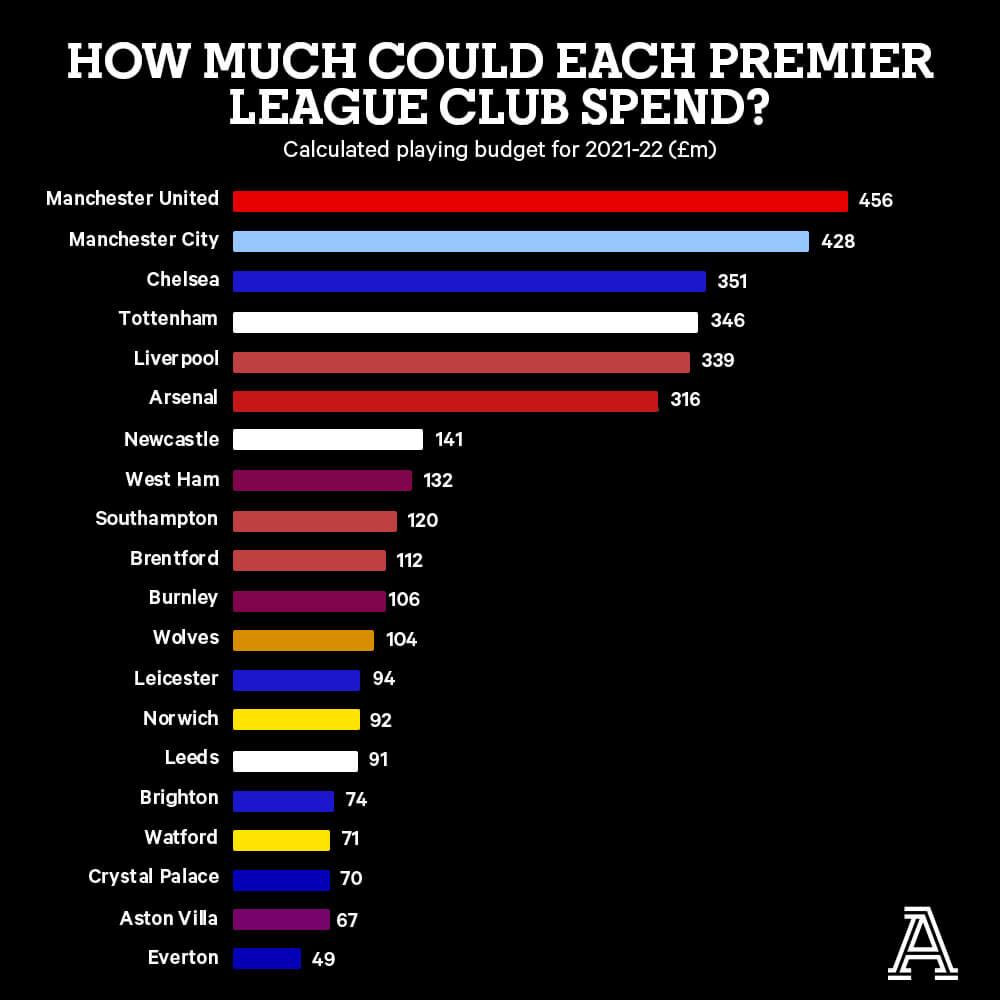

The Athletic has looked at the accounts of the 20 clubs who will form the Premier League in 2021-22 and has applied a much simpler and cruder version of the formula used by La Liga above (we don’t have an army of analysts to crunch the numbers) to see the potential budgets that clubs would face in the forthcoming season.

In the case of, for example, Manchester United, we started with a full year’s revenue using 2018-19 as a base point. This was because in 2019-20 the season had not finished by June 30, when the accounts were published, and so broadcast and some other revenues were reduced to reflect this.

Day-to-day running costs excluding wages but including finance costs were then subtracted, and a final adjustment was made in respect of net sums that were due to be paid in the next 12 months, according to each club’s balance sheet.

Adjustment is then made for profits on player sales to take into account trading strategy, which would benefit clubs such as Brentford who have had a very successful recruitment and sale model.

Some clubs owed large amounts to owners that were theoretically repayable in the next 12 months, such as Newcastle with Mike Ashley and Brighton with Tony Bloom. In respect of these clubs a further adjustment was made on the basis that the owner was in practice unlikely to demand their money back.

On the basis of these calculations, which must be stressed are far more basic than the complexity of calculations used by La Liga, the Premier League spend on wages and transfers would fall by about £430 million, compared to the most recent accounts for 2019-20.

Those clubs that have had historic good control over costs would be rewarded, and the Big Six would still enjoy a substantial financial advantage over the other clubs. At the bottom end of the table, the sight of Everton might initially surprise but the club has spent a lot in recent seasons and this has resulted in high wages and amortisation fees, which would be clawed back by a tighter budget for 2021-22.

If such rules were to be introduced there would have to be a transition period in which clubs would adjust their spending behaviour to avoid having to face a “cliff face” fall in spending.

The introduction of such a scheme might be seen as a disincentive for ambitious owners such as Farhad Moshiri at Everton and Wes Edens and Nassef Sawiris at Villa. Unless initial spending was turned into instant success, and thus revenue, they would be likely to be faced with much reduced budgets earlier than at present.

The fear among critics is that introducing such rules into the Premier League will “bake in” the existing financial advantage that the Big Six/Five/Four (delete as necessary based on whether you consider Arsenal and Spurs to be legitimate challengers to the other large clubs) possess. This will result in a disincentive for new owners to invest in Premier League clubs and could in the longer term make the product less unpredictable, and potentially less interesting to viewers.

Regardless of the rules, there are likely to be winners and losers. As soon as any changes to cost control are introduced expect to see accountants and lawyers at some clubs beavering away to find weaknesses and loopholes that can be exploited. Any independent regulator is going to need to be adept at Whack-A-Mole as a series of challenges arise to new measures.

133

133