Adèle Haenel accuses director Christophe Ruggia of "molestation" and "sexual harassment" when she was between 12 and 15 years old. Her story is supported by numerous documents and testimonies. Mediapart traces her long journey from "impossible speech" to "silence that became unbearable". The filmmaker "categorically" contests the facts.

First of all, there was the deep, tenacious, indelible "shame". Then there was the cold "anger" that has not left her for years. And finally, there was the appeasement, "little by little", because we had to "get through it all". In March 2019, anger was rekindled, "in a more constructed way", on the occasion of the HBO documentary on Michael Jackson, which reveals damning testimonies accusing the singer of paedocriminality, and reveals a mechanism of control.

"It made me change my perspective on what I'd been through," explains actress Adèle Haenel, "because I'd always forced myself to think it was a love story without reciprocity. I had adhered to his fable of "we're not the same, other people couldn't understand". And then it also took that time for me to be able to talk about things, without making an absolute drama out of it either. That's why it's now. »

This morning of April 2019, the actress takes the time to choose every word to tell. She pauses for long periods of time, then resumes. But the voice does not hesitate. "I'm really angry," she says. "But it's not so much about me, how I survive or don't survive this. I want to tell about an unfortunately banal abuse, and to denounce the system of silence and complicity that makes it possible. "Telling has become a necessity, because "the pursuit of silence had become unbearable", because "silence always works in favour of the guilty".

Adèle Haenel decided to put the words publicly on what she "clearly considers to be paedophilia and sexual harassment". She accuses director Christophe Ruggia of inappropriate sexual behaviour between 2001 and 2004, when she was between 12 and 15 years old, and he was between 36 and 39 years old. At Mediapart, the actress denounced the filmmaker's "strong hold" during the shooting of the film Les Diables, followed by "permanent sexual harassment", repeated "touching" of the "thighs" and "torso", and "forced kisses in the neck", which allegedly took place in the director's apartment and at several international festivals. She does not wish to take the case to court, which, according to her, generally speaking, "condemns the aggressors so little" and "one rape in a hundred". "Justice ignores us, we ignore justice. »

Contacted by Mediapart, Christophe Ruggia, who refused our interview requests, did not wish to answer our specific questions. But he made it known, via his lawyers, Jean-Pierre Versini and Fanny Colin, that he "categorically refutes having exercised any kind of harassment or any kind of touching on this young girl who was then a minor". "You sent me last night [on the evening of 29 October, in the wake of a phone call from her lawyer - editor's note] in 16 points a lengthy questionnaire on what would have been the professional and emotional relationship I had more than fifteen years ago with Adèle Haenel, whose great talent I was the "discoverer" of. The systematically tendentious, inaccurate, romanticized, sometimes slanderous version you have sent me does not put me in a position to give you answers," he reacted in a written statement.

During our seven-month investigation, we spoke with some 30 people and gathered many documents and testimonies that support the actress's story, including letters from the director in which he tells her, among other things, of his "love", which "has sometimes been too much to bear". Several people tried, on the set, and then over the years, to warn about the director's attitude with the actress, without being heard, according to them.

Adele Haenel, in Paris. Isabelle Eshraghi for Mediapart

Christophe Ruggia, 54, has become one of the voices of French independent cinema, as much - if not more - through his militant commitments as through his filmography. In particular, he has defended the cause of refugees, intermittent workers and filmmaker Oleg Sentsov, who was imprisoned for five years in Russia. Co-president of the Society of Film Directors (SRF) until June, he is described by those who know him as a "pasionaria that wants to save the world", "a director of permanent intensity", whose films feature children with bumpy routes.

It was in his second feature film, Les Diables (2002), that Adèle Haenel made her debut. Today, at only thirty years of age, she has already won two Césars and 16 films at the Cannes Film Festival, under the direction of prestigious filmmakers such as the Dardenne brothers, Céline Sciamma, André Téchiné, Bertrand Bonello and Robin Campillo.

The story begins in December 2000. Adèle Haenel is eleven years old, her days are divided between her fifth grade class in Montreuil (Seine-Saint-Denis), her drama classes and her judo training. Accompanying her brother to a casting, it was she who landed the role for Les Diables. "The kid was exceptional, there weren't two like her," recalls Christel Baras, the film's casting director, who remained friends with her recruit.

At the time, the girl, like her parents, was on cloud nine. "It was a fairy tale, it was completely amazing that it came down on us," says her father, Gert. "I feel inflated with a new importance, maybe I'll make a film," the actress wrote in her personal notebooks, written afterwards in 2006, and which Mediapart was able to consult. In it, she evokes the "novelty", the "dream", the "privilege" of "being alone on stage, at the centre of the attention of all these adults", "to stand out from the crowd". Her "passion" for theatre. And her "little discussions with Christophe [Ruggia]", who "drove her home in his car", "always invited her to eat out", even though she "was ashamed the first time" because she didn't have enough money to pay.

"For me, he was a kind of star, with a side of God descended to Earth because there was cinema behind it, the power and the love of acting," the actress explains today. Her family - the intellectual middle classes - "suddenly became exceptional," she recalls. "And I go from being a commonplace child to a promise to be "the future Marilyn Monroe," according to him”. At home, Ruggia is received "with all honors." "He was a good director, left-wing, he had just made Le Gone du Chaâba, a very good film. We trusted him," says his mother, Fabienne Vansteenkiste.

The script of Les Diables, disturbing and punctuated with nudity, does not repel parents. The film features the incestuous love of two runaway orphans, Joseph (Vincent Rottiers) and his sister Chloé (Adèle Haenel), autistic, dumb and allergic to physical contact. It leads to the discovery of physical love by the two pre-adolescents. Christophe Ruggia has never made a mystery of the partly autobiographical character of this film, "a compromise between a harsh reality experienced by [his] two best friends and his own," he said in the press.

Director Christophe Ruggia with actress Adèle Haenel, on the set of the movie "Les Diables". Excerpt from the making-off of the film.

The performance of the two young actors on screen was obtained thanks to a six-month work before the shooting. These particular exercises, carried out by the filmmaker and his assistant director - his sister Véronique Ruggia - were intended to "give them confidence so that they could play difficult things: autism, awakening to sensuality, nudity, discovering their bodies," he explained at the time (TéléObs, 12 September 2002). "The three of us have developed extraordinary connivance". All in all, from the preparation to the promotion of the film, it is "almost a year in which the children are detached from their families," he analysed at the time. The ties are very strong. Several of the actress's close friends are convinced that the director's "hold" has been forged in this "conditioning" and "isolation". This "hold" would then have paved the way, according to the actress, to more serious events after the shooting.

Some of the twenty members of the film crew who were approached say they "have no memories" of this old filming or did not wish to answer our questions. Others say that they "didn't notice anything". This is the case, for example, of producer Bertrand Faivre, actor Jacques Bonnaffé (who was on the set for a few days), or the film's editor, Tina Baz. Tina Baz remained close to the filmmaker, who described him as "respectful", "incredibly affectionate", "with an absolute investment in his work" and an "unambiguous paternal relationship" with Adèle Haenel.

Conversely, many portray a director who is both "all-powerful" and "childish", "immature"; "stifling", "vampiricating", "monopolizing", "invasive" with children, isolating himself in a "bubble" with them. Nine people describe a "hold", or a strong "ascendancy" or "manipulation" relationship between the filmmaker and the two actors, who perceived him as "Santa Claus".

During the shooting, which began on June 25, 2001, Christophe Ruggia reportedly gave special treatment to twelve-year-old Adèle Haenel, who, according to several testimonies, was "protected", "cared for" and "too sheltered". "It was special with me," confirms the actress. "He clearly played the love card, he told me that the film adored me, that I had genius. I may have believed that speech for a moment. »

"I've always seen how close they are," says actor Vincent Rottiers, who has remained friends with the filmmaker. He remembers that "Adèle kept sticking to him, like a first in the class with her teacher" and that "Christophe took more time with her, put her in conditioning". "There was nothing but for her, to the point that I was sometimes jealous. But I thought it was special because she played an autistic girl. Looking back, I see it differently. »

Eric Guichard, the cinematographer, did not notice any "inappropriate gesture" but said he "rarely" saw "such a fusional relationship" between the filmmaker and the young actress, who was "inhabited by her role", "captivated by Christophe, very invested" and "confided only in him". He describes an "obvious ascendancy" of Ruggia, but which he placed "at the level of the making of a cinema film" and attributed "to the difficulty of the character of Adele".

For the actress Hélène Seretti, hired as an actor's coach on the set and who never lost contact with Adèle Haenel, the filmmaker "stuck too much" to the girl. "He was tactile, put his arms on her shoulders, sometimes gave her kisses. For example, he would ask her: "And what are you having for lunch, my darling?"" she recalls. Little by little, I told myself that this was not a relationship that an adult should have with a child, I didn't feel it clear, it bothered me. "Not quiet", she says she remained "alert". But she's confined to the role of "nanny", away from the set. " Christophe Ruggia had a privileged relationship with the two children, so he told me clearly : " You don't take care of them, I worked for months with them to prepare this shooting. " When he was preparing the scenes, he kept me out of the way," she claims.

Dexter Cramaix, who worked in the production department, remembers the relationship between the director and his two young actors as "not in the right place", "too emotional" and "exclusive", "beyond the purely professional". "Between us, we told each other that something was not right, that there was something wrong. Directors are often told that they must be in love with their actresses, but Adele was twelve years old. »

Director Christophe Ruggia on the shooting of the film "Les Diables" (2002). Laëtitia, the general manager of the film - who left the set at the end, after a burn-out - confirms: "Christophe's relationship with Adèle was not normal. We had the impression that she was his fiancée. We were hardly allowed to approach her or talk to her, because he wanted her to stay in her role at all times. He was the only one who had the right to really be in contact with her. We were very uncomfortable on the team. »

Edmée Doroszlai, the script girl, says she shared the same feeling with one of her colleagues: "I said, 'Look, it looks like a couple, it's not normal." "She says she "sounded the alarm" when she saw "the exhaustion and mental suffering of the children". "It went too far. To protect them, I had the filming stopped several times and I tried to contact the child services. "He was manipulating the children," says photographer Jérôme Plon, who left the shoot after a week with the impression of a "somewhat guru-like operation" and a filmmaker taking "a bit of possession of people. Worried, he says he talked about it "to a friend who is a child psychanalyst". "I didn't move, he was angry at me for not consenting."

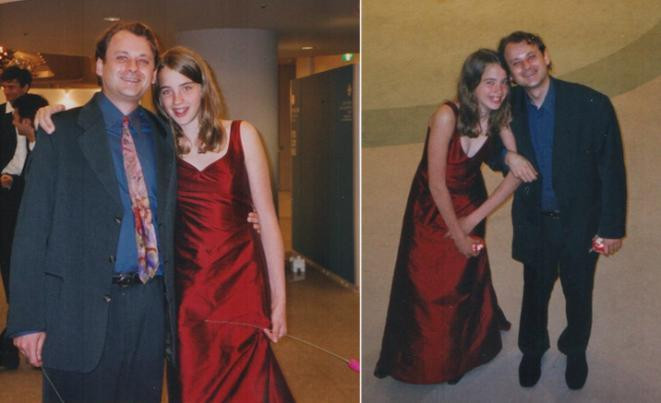

Adèle Haenel with director Christophe Ruggia and actor Vincent Rottiers, at the Yokohama festival (Japan), in June 2002. Document Mediapart

How to distinguish, on a film set, the subtle border between a particular attention paid to a child who is the main actress in the film, a relationship of hold and a possible inappropriate behaviour? At the time, many crew members struggle to put a word on what they observe. Especially since none of them had witnessed any explicit "sexually explicit gesture" by the filmmaker towards the actress. "I was always oscillating between 'It's not going well at all' and 'Maybe he's just fascinated,'" recalls Hélène Seretti, 29 at the time. "I was young, I didn't trust myself. Today it would be different. »

The stage manager, Laetitia, also had her doubts: "It's very complicated to tell yourself that the director you work for is potentially abusive, that there's manipulation. Sometimes I used to think to myself, 'Did I dream? Am I crazy?' And no one would have the idea of interfering in his relationship with the actors, of daring to say a word, because it's part of a creative process. Hence the possibility of abuse - be it physical, moral or emotional - on the set."

Two members of the film crew told Mediapart that they were kept away after voicing concerns about the actress. Hélène Seretti says she "alienated" the filmmaker by expressing her doubts. One morning, she seized the opportunity of a "bad night" spent by the actress, after her mother had asked her about Christophe Ruggia's behaviour, to talk to the filmmaker. "I tried to explain that Adèle wasn't well, that it had gone too far, that we couldn't go on like that. And he said, "You want to fuck up my film, you don't realize the special relationship I have with them." "From that point on, she claims that he "never spoke to her again" and that "the rest of the shooting was not easy". She says she tried to raise her fears with several members of the crew. She was told that "it's the cinema, it's the relationship with the actor" and that "the director is the boss". "We didn't dare challenge the director, I was afraid and I didn't know what to do or who to talk to," she says today.

The casting director, Christel Baras, says she would have been "ousted" from rehearsals, after a remark in the summer of 2001, before shooting. "We were in the entrance of Christophe's apartment. Adele was sitting on the couch further away. He wanted me to go away, to leave them. I was very uncomfortable, disturbed, it was the way he was looking at her, what he was saying. I said to myself, "Now it's getting out of hand," she relates. I didn't imagine anything sexual at the time," she says, "but I could see his hold on the girl. »

On leaving, she would have "looked the filmmaker straight in the eye" and warned him: "She's a little girl, a little girl! She's twelve years old! "After this episode, Christophe Ruggia would have told her that he "didn't want her on the set anymore". A few years later, in retrospect, she interpreted this decision as "a ban" because she was "dangerous". Was the casting director, with her strong personality, considered too intrusive on the set, or was she shielding the exclusive relationship that the director would have liked to establish with his actress?

In any case, after the film's release, Christel Baras' "uneasiness" will be reinforced when she meets the girl "two or three times" at the director's house. Notably on a Saturday evening, while passing by unexpectedly looking for a DVD. "It was 8:00 to 10:30, I was embarrassed, and I said, 'What the fuck are you doing here Adele, go home, have you seen the time at last?" ", she recalls. According to her, "Adele was in his grip, every time she went back. "Christel Baras would then work with the director again on another film, with adults.

The director Christophe Ruggia and the actors Adèle Haenel and Vincent Rottiers, on a shot of the whole team of the film "Les Diables", on the set, in the summer of 2001 © Document Mediapart

Our witnesses invoke the posture of the "almighty director" to explain that no one tried to speak out against his behaviour. Some say they were afraid that their contract would not be renewed or that they would be "blacklisted" in this precarious environment; others say they blamed his attitude on the "special relationship between the director and his actors", his "working methods" to "encourage his actors to play". And most of them say they were concerned about a shoot that they described as "difficult", "harassing", "with little money" and "six days a week".

The actress's mother herself expressed her concerns. At Mediapart, Fabienne Vansteenkiste recounts the "uneasiness" that overwhelmed her when she came to the filming in Marseilles. "On the Old Port, Christophe was with Adèle on one side, Vincent on the other, his arms over each other's shoulders, kissing them. He had a strange attitude for an adult with a child. "At the time, she didn't say anything, thinking that she "doesn't know the film business". But on the way home, worried, she stops at a gas station to find a phone, and calls her daughter to ask her "what's going on with Christophe". "Adèle sent me off on a wild goose chase, to the tune of "But my poor thing, your mind is really in the wrong place," recalls her mother. The following night, the schoolgirl had an unusual nervous breakdown. "I wasn't at all calm, I screamed like some kind of animal, I was wounded. The next day I was uncomfortable on the set, we did the scene over and over again even though it was simple," says Adèle Haenel. Hélène Seretti hasn't forgotten this episode: "There was a dichotomy in her, she felt the trouble - without being able to name it yet -, and at the same time she kept repeating that she wanted to see this film through to the end. »

It was after the shooting, which ended on September 14, 2001, that the thirty-six-year-old filmmaker's exclusive relationship with the twelve-year-old actress "slipped into something else," says Haenel. According to her testimony, "touching" would have taken place on the occasion of regular meetings, on weekends, in the Parisian apartment of the director, where her father sometimes took her. Christophe Ruggia, who owns a DVD library, takes the young actress's film culture in hand, reads the scripts she receives and advises her. According to her account, the filmmaker "always proceeded in the same way": "white chocolate Fingers and Orangina" placed on the small table in the living room, then a conversation during which "he slipped", with gestures that "little by little, took up more and more space". Adèle Haenel's memories are precise: "I would always sit on the sofa and he would sit opposite me in the armchair, then he would come over to the sofa, stick to me, kiss me on the neck, smell my hair, caress my thigh as he went down to my sex, start passing his hand under my T-shirt towards my chest. He was excited, I pushed him away but it wasn't enough, I always had to change places. "First at the other end of the couch, then standing towards the window, "looking like nothing", then sitting on the chair, and "as he was following me, I ended up sitting on the footrest which was so small that he couldn't come close to me," she says.

For the actress, it is clear that "he was seeking to have sex with [her]". She points out that she cannot remember "when the filmmaker's gestures stopped" and explains that his "caresses were something permanent". She recounts the "fear" that "paralyzed her" in those moments: "I didn't move, he was angry with me for not consenting, it triggered crises on his part every time", in the register of "guilt", she says. "He assumed that it was a love story and that it was mutual, that I owed him something, that I was a bitch not to play the game of that love after all he had given me. Every time I knew it was going to happen. I didn't want to go, I felt really bad, so dirty that I wanted to die. But I had to go, I felt like I owed it to him. "Her parents, they, "don't ask questions. " "I think to myself, she watches films, it's great that she has this film culture thanks to him," recalls her mother. Vincent Rottiers explains that he too went "often" to Ruggia's house, to talk about "cinema and current affairs", sometimes "with friends": "It had become family, Christophe. My cinema father. "Adèle was sometimes already there when I arrived, I thought it was strange, I asked myself questions, but I didn't understand. "Christophe Ruggia, for his part, "categorically refutes" to Mediapart any "harassment of any kind or any kind of touching".

According to the actress, the director would have had the same gestures in another closed room: the hotel rooms of international festivals, which the filmmaker skimmed with his two young actors after the release of the film in 2002: Yokohama (Japan), Marrakech (Morocco), Bangkok (Thailand). Photos, hotel etiquette, programmes, press reviews: in a blue folder, the actress has kept everything from this "promo" during which she discovered with fascination, at the age of 13, the plane, the beach, the luxurious buffets, the crackling flashes, the autographs to sign. But she hasn't forgotten the "strategies" she developed to escape from "his touch" in the "promiscuity" of hotel rooms: "When I walked into a room, I knew where to stand, so that he wouldn't come and stick to me. "She details the wide windowsill of the Inter-Continental Hotel in Yokohama in June 2002, on which she sat, "because [she] didn't want to be on the bed next to him. "But he would come up to me, he would glue me, he would try to touch me, he would say 'I love you'," she says. She evokes Christophe Ruggia's "declarations" and "I love you", openly, "at parties", his "extreme scenes of jealousy". But also the state of "anguish" she felt: "One morning I woke up and started to 'paranoid', I said to myself, 'I didn't fall asleep in that bed." "On several series of shots from the festival, which Mediapart found, we see the director in a tuxedo holding the actress by the hip, long evening dress and missing milk teeth

Director Christophe Ruggia with actress Adèle Haenel at the Yokohama International Film Festival (Japan) in June 2002. Document Mediapart

Adèle Haenel also remembers a scene that would take place at the Marrakech festival in September 2002: the filmmaker would have been "angry" to discover that she had "eaten the little chocolate offered by the hotel" while he was making "a declaration of love to her in her room". "He kicked me out of the room and then reopened it. He told me he loved me, that he was completely crazy. I found myself there with this drama. I pulled an all-nighter for the first time in my life. »

In June 2004, at the age of fifteen, she went off on her own with Christophe Ruggia to the French Film Festival in Bangkok. She remembers pushing away her hand again, which "squeezed [her] hip in the tuk-tuk". "It made him angry, and he wanted me to feel guilty," she says. In a letter to the actress on July 25, 2007, the filmmaker recounts the "great trip with lots of moments, but it completely destabilized him" and the "problems" that had arisen in Thailand. What "problems" was he talking about? Asked about this, Christophe Ruggia did not answer.

That year, he had written a screenplay "for [her]", whose main characters were called "Adele and Vincent", and that he wanted to "offer her [...] on her sixteenth birthday", he said in his letter. He explains that he was "terrified" at the idea that the actress did not want to participate in this new film, "because of me, (considering how you treated me at times there)," he writes. According to the actress, the director had a great deal of control over her at the time. Even to the point of regulating trivial things, she says, such as her habit of running her tongue across her lip. "He told me to stop, in a way, 'It's too sexy, you don't realize what you're doing to me." »

Director Christophe Ruggia with actress Adèle Haenel at the Yokohama Film Festival (Japan) in June 2002. Document Mediapart

Several documents and testimonies collected by Mediapart support Adèle Haenel's story. First of all the confessions that Christophe Ruggia himself is said to have made in spring 2011 to a former companion, the director Mona Achache. "He confided to me that he had feelings of love for Adèle", during the promotional tour of Les Diables, explains the director, who is not an acquaintance of Adèle Haenel, to Mediapart. She says that after questioning him insistently, he would have ended up recounting a specific scene to her: "He was watching a film with Adele, she was lying down with her head in his lap. He had pulled his hand up from Adele's belly to her chest, under the T-shirt. He told me that he saw a look of fear in her, eyes wide open, and that he too had been frightened and pulled his hand out. »

Mona Achache says she was "stunned" and "uncomfortable" by "his way of telling the story": "He felt strong, loyal, upright, to have been able to withdraw his hand. He was trying to turn it into a joke by telling me that he was lost in love with her and that she was driving him crazy. "When confronted with his questions, the filmmaker would have been "a little elusive", "minimizing the thing". "He didn't realize that having interrupted his gesture didn't change anything to the trauma he may have caused beforehand, she recalls. He didn't question the very principle of these meetings with Adele, or the genesis of a relationship that makes it possible for a child to be languished on his lap while watching a movie. He remained focused on him, his pain, his feelings, without any awareness of the consequences for Adele of his general behaviour. "The director explains that she was "flabbergasted" when she abruptly left him, without telling him the reason, and wished she would never see him again.

She says she "kept silent", because it "did not seem right to speak in Adèle Haenel's place", especially since she did not know what "Christophe Ruggia had wanted to tell her". At the time, she opened up to a close friend, the filmmaker Julie Lopes-Curval. We were at Mona's, she confided to me that it hadn't been clear with Adèle Haenel," the director confirmed to Mediapart. She didn't tell me everything, but she was embarrassed about something. There was a discomfort, it was obvious... " Asked about Mona Achache's story, Christophe Ruggia did not answer.

Other testimonies reinforce the actress' story. Like the concerns expressed twice by Antoine Khalife, who represented Unifrance at the Yokohama festival in 2002. First in January 2008, at the Rotterdam Film Festival, with director Céline Sciamma, who came to present her film Water Lillies, in which Adèle Haenel is starring. "I didn't know him," says Sciamma, "I really like your film and I was very relieved to hear from Adèle Haenel, happy to see that she wasn't dead. He tells me he was very worried about her, he tells me about Yokohama in great detail, Christophe Ruggia who made her dance in the middle of the room, which was declarative. He was moved. »

Ten months later, on the sidelines of a Unifrance event in Hamburg, Antoine Khalife will also open himself to Christel Baras, during a car trip. "He says to me: "I'm very happy to see you, because I've always been very annoyed about something: I promoted Les Diables in Yokohama, I never understood the relationship Christophe Ruggia had with this young actress. We couldn't talk to her, we couldn't get close to her. What happened?" the casting director rewrote. I said to myself, "There you go, I'm not crazy." "When contacted, Antoine Khalife did not wish to express himself.

Adèle Haenel, director Christophe Ruggia and actor Vincent Rottiers, at Cannes in 2002. Document Mediapart

Another element: two letters addressed by the director himself to the actress, in July 2006 and July 2007, show the feelings he had for her. In these letters, which Mediapart obtained, Christophe Ruggia evokes his "love for (her)" which "has sometimes been too heavy to bear" but which "has always been absolutely sincere". "I miss you so much, Adèle! I miss you so much, Adèle!", "You are important to me", "The camera loves you madly", he writes, explaining that he will have to "continue to live with this wound and this lack", while hoping for "reconciliation". "I've even asked myself several times if I wasn't the one who was going to stop making films. I still ask myself that sometimes, when I'm in too much pain. »

Some time earlier, in 2005, Adèle Haenel, now a high school student, told Christophe Ruggia that she had stopped all contact with him after yet another afternoon spent at his home. "That day, I got up and said, 'This has got to stop, it's going too far." I couldn't assume to say more. Until then, I hadn't put the words in, so as not to offend him, so that he wouldn't see himself abusing me. "According to the actress, the director was embarrassed that day. " He wasn't feeling well, he said, 'I hope it's okay." »

Benjamin, her boyfriend during the high school years, confirms: "There was a meeting at Christophe Ruggia's house that was different from the others, which forced her to tell me about it. She was disturbed. "The actress, who had at first totally "compartmentalized her two lives" and cultivated, according to the young man, "an embarrassment, a feeling of shame, of guilt" about Ruggia, recounts to him on this occasion the director's "guilt-ridden declarations of love", his "permanent hold" and "scenes where she had been uncomfortable, alone, at his place". The high school student then puts "pressure" on her to cut all ties.

For Adèle Haenel, it was "the incomprehension, even clumsy", of her friend that "was the spark to give [her] the strength to leave". "I had met this boy, started to have a sexuality and the fable of Christophe Ruggia was no longer valid. »

At the time, the confused teenager "saw no other way out than for him or her to die or give up everything. It was finally the cinema that she gave up. The actress claims to have sent a letter to the director at the beginning of 2005, in which she explains that she "no longer wants to come to his house" and that she "stops making films". A letter that was written with the feeling of "giving up a lot of things" and "a part of [herself]", she confides to Mediapart: "I had acting in my gut, that's what made me feel alive. But for me, it was him the cinema, he was the one who made me there, without him I was nobody, I was falling back into absolute nothingness. »

Adèle Haenel and the actor Vincent Rottiers in the film "Les Diables" (2002), in which she plays an autistic girl.

For his part, the director, who wrote to her having received her letter "in his heart", tries to reconnect, via his best friend, Ruoruo Huang, then 17 years old. "We had lunch together at the Cantine de Belleville," she recalls. I didn't know anything about it. In the middle of the discussion, he told me that Adele wasn't speaking to him anymore, he tried to get news and implicitly to pass on a message. »

Adèle Haenel leaves her agent, doesn't follow up on any script or casting, and cuts ties with the film industry. "I chose to survive and go on my own," she says. This radical decision plunges her into an "enormous uneasiness": depression, suicidal thoughts, and a visceral "fear" of running into the filmmaker. This will happen on three occasions - in a demonstration near the Sorbonne in March 2006, in a bakery in 2010, at the Cannes Film Festival in 2014 - provoking in her, according to two witnesses, "a panic", "an upheaval", "an intense reaction". "I continued to be afraid in her presence, that is to say in concrete terms: my heart beating fast, my hands sweating, my thoughts blurring", the actress explains. She evokes ten years "at the end of her nerves", when she could "hardly stand upright" anymore.

Her personal notebooks bear the traces of these anxieties. In 2006, the seventeen-year-old tells of the "monstrous mess in [her] head," and says she needs to write "to remember, to clarify things," because she has "a bit of trouble remembering exactly what happened. In the year 2001, it says: "I am becoming a center of attention. "Followed, for 2002, by these annotations: "Festival + Christophe weird => I feel lonely, strange. "Then: " 2003: I have a secret, I never talk about my life. I'm in an adult world. [...] 2005: I don't see Christophe anymore. "Sometimes I think I'm going to manage to say everything [...] I can't stop thinking about death," she wrote in 2006.

Why didn't her entourage perceive these signals? Her family initially saw it as a teenage crisis. Her brother Tristan says he blamed his sister's "estrangement" and "anger" on "puberty," not without noticing "something strange" in the director's behavior and his sudden disappearance: "At one point, Christophe was just not there anymore. "His parents emphasize the blind trust placed in the director during all these years. Her father says he "became aware much later of the hold that Christophe Ruggia had on her. For Adele, he was the alpha and omega, and suddenly she didn't want anything more to do with him. But it was difficult to talk to her as a teenager. Her mother explains that she was absorbed by a busy job and the worries of everyday life: "At the time I was a teacher, I also made commercials, I was involved in politics and I was never around. »

It was when the teenager was frightened when she received a call on her home phone in February 2005 that she said she "understood" that there had been "abuse". "Adèle suddenly became tense and said, terrified, "I'm not here! Answer that I'm not here!" When she saw it was one of her friends, she relaxed and took the call. I asked her, "Were you afraid it was Christopher?" She said, "Yes, but I don't want to talk about it." " "Very worried," her mother will try several times to put the subject on the table, without success.

I felt so dirty at the time, I was so ashamed, I couldn't tell anyone, I thought it was my fault," says the actress, who was also afraid of "disappointing" or "hurting" her parents. "Silence has never been without violence. Silence is an immense violence, a gagging. »

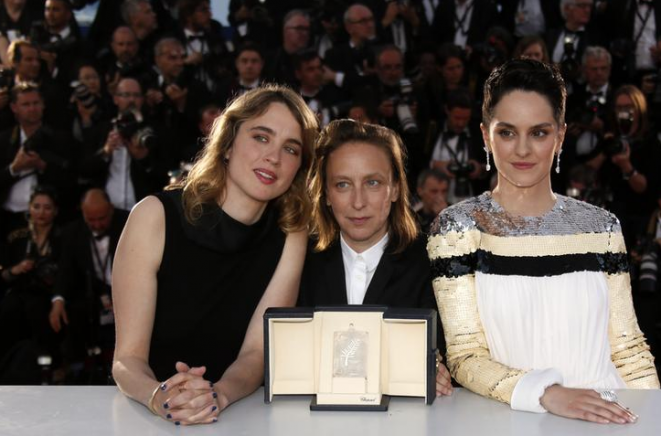

Adèle Haenel, director Céline Sciamma and actress Pauline Acquart on the shooting of the film "Water Lillies", in 2006.

The actress explains that she has immersed herself "thoroughly" in her studies, "so that no one will ever think of [her] place again. I could have learned Thai boxing, I studied philosophy. During this long journey, she says she has received "no support from anyone" and has gone through "loneliness, guilt". Until her meeting with the director Céline Sciamma and her return to cinema with Water Lillies, described by many of her relatives as a step towards "rebirth".

It was Christel Baras, "sick of this mess and of having recruited Adele for Christophe Ruggia's film", who contacted her again for this film in 2006. The casting director is certain, "it's a role for Adèle. With this film, we're going to get back together, everything else will be behind us, it will be nothing but positive". "There are only women here, and the director is extraordinary," she slips into the teenager, who has just turned 17. "I came back, fragile, but I came back," says Haenel.

By accepting the role, the actress immediately tells Céline Sciamma about "problems" that arose in her previous film, and confides in her for the first time. She tells me that she wants to make the film, but that she wants to be protected, because something happened to her on her previous film, that the director didn't behave well," she explains. She doesn't go into details, she finds it difficult to express herself, but she tells me about the consequences that this had, her loneliness, her stopping making films. I understand that I am the depositary of a secret. »

This "secret" is revealed at the end of the shooting of Water Lillies, in which two members of the Devils' team take part: Christel Baras and Véronique Ruggia, coach of the actresses. Céline Sciamma remembers discovering, appalled, that the two women "wondered, worried, how far it had gone, if Christophe Ruggia had had sexual relations with this child". "Each had been living with this question for years, and remained in secrecy and guilt over the story. I could also see the admiration and the hold that Ruggia generated, because he is the director, their employer, their brother, their friend. "During their conversation in mid-October 2006, Ruggia "collapsed, very affected," says the director. She would have asked him"if Adèle had said no", adding: "You have the right to fall in love, but on the other hand, when you say no, it's no. »

Céline Sciamma, who then begins a love relationship with Adèle Haenel, says that she herself "became fully aware of the seriousness of the facts" one evening it again. It was very impressive," she recalls. Adèle went crazy, fainted, screamed. It was a pain... I'd never seen her like that. »

The 27-year-old filmmaker encourages her "not to remain silent about this, not to go unpunished, to speak out". "The idea emerges to talk about it to Christophe Ruggia, but also to those in charge around him, and to the people around us. »

Adèle Haenel decides to speak: to Hélène Seretti, to Christel Baras, to Véronique Ruggia. Sometimes minimizing the reality of the feelings, the acts and the consequences - like many victims in this type of case. She remembers her "confusion" by confiding in Véronique Ruggia. "We talked for a long time at her home. I really wasn't well, embarrassed to have to tell her that, I couldn't talk too much, and I apologised a lot to Christophe, saying: "No, but it's OK, he was just a bit out of sorts," the actress recalls. Véronique was affected, she was ashamed and guilty I think, but we still had to put the seriousness of the thing into perspective. »

When contacted, Véronique Ruggia confirmed that she had discussed it with Adèle Haenel and Céline Sciamma. "I fell off the wagon," she recalls, explaining that she understood that there had been "no action". She concedes a "disturbance" in her memories: "It shocked me so much that I certainly put a handkerchief on the memory of many things. She recalls that the actress told her that she "told Christel [Baras] about it and asked the question, 'What were the adults doing on the set? "I found out a lot of things that day that I hadn't been aware of at all. "I had talked about it with my brother at the time Adele made those statements," she says, without wanting to say any more before "discussing it with him". "I'd rather have him talk to you. "

Adèle Haenel claims to have deposited, in 2008, with her partner Céline Sciamma, a new letter in Christophe Ruggia's mailbox, in which she claims to have mentioned the problem. The letter denounced Ruggia's fiction and recounted the events in their raw and cruel truth," she said. Adèle described the facts, the gestures, the avoidance strategies. She confronted him with his actions. It was deflagrating. "This letter will remain unanswered. Questioned on these two points, Christophe Ruggia didn't answer.

Adèle Haenel, director Céline Sciamma and actress Noémie Merlant at the Cannes Film Festival for their film "Portrait of the Young Girl on Fire" on May 25, 2019. Reuters

Six years later, in 2014, Céline Sciamma was elected head of the Société des réalisateurs de films (SRF) along with Christophe Ruggia. She confides her "unease" to several members of the association, but does not wish to act in Adèle Haenel's place. For her part, the actress tries to tell her story to common acquaintances sitting in the SRF, without being heard, according to her. "What made it impossible to speak for so long was that I was told, even before I said anything, that Christophe was "a good person", that he had "done so much for me" and that without him I would be "nothing", she relates. People don't want to know, because it involves them, because it's complicated to tell yourself that the person you laughed with, smoked cigarettes with, who's committed to the left, did this. They want me to keep up appearances". The actress says that over the years, she has been subjected to remarks that fluctuate between uneasiness, denial and guilt. Friends from the film world, sometimes even feminists, close the discussion with "You can't say that" or "He's a saint". His father urged him "to forgive" and above all not to publicize the affair.

Others have since offered to help. "I'm ashamed, I didn't take the measure, I didn't understand. What can we do? "asked director Catherine Corsini, the current co-president of the SRF, more recently. The filmmaker told Mediapart that she "learned two years ago that Adèle had wanted to denounce Christophe Ruggia's inappropriate behaviour to members of the SRF, who did not know what to do. For many, it was unimaginable. And it was difficult to intervene without knowing what Adèle Haenel wanted to do. Celine Sciamma was suffering from the situation". When she heard about the actress' testimony in detail and her "suffering" in April, she was "overwhelmed". "As is often the case, everyone closed their eyes or did not ask questions. This must be questioned by each of us individually. »

Publication of the SRF Instagram account.

Year after year, the director will be re-elected to the Board of Directors of the prestigious SRF and will serve several times as co-chair or vice-chair between 2003 and 2019. He will, for example, co-sign the press release welcoming the "wind of change" after the Harvey Weinstein affair, or the press release questioning the Cinémathèque Française's "position statements" after the controversy surrounding its retrospectives of Roman Polanski, accused of rape, and Jean-Claude Brisseau, convicted of sexual harassment.

Adèle Haenel and Céline Sciamma claim to have alerted another person: Ruggia's producer Bertrand Faivre, on 8 December 2015, on the sidelines of the IFCIC award ceremony at the China Club in Paris. That evening, the producer started a conversation about Les Diables. He is surprised that the actress never talks to journalists about this first film. He is especially pleased to have, at the Marrakech festival, protected the girl from a photographer who asked for a photo session alone with her. "He bragged that he had saved me from the potentially paedophile behaviour of this photographer. I lashed out, and I said, "No, you didn't, you didn't protect us!" Then I said that Christophe Ruggia had behaved badly towards me," recalls the actress, then aged twenty-six.

Both Haenel and Sciamma have not forgotten the producer's confusion: "flabbergasted", "disturbed", "he couldn't believe it", "he said, 'It's not possible'". "It is, as she has just told you extremely clearly, hear her," Céline Sciamma replies, in an aside, according to her testimony. "Now you know. You're going to have to ask yourself the questions."

Questioned by Mediapart, Bertrand Faivre recalls being "stunned" by Adèle Haenel's "anger" and "violence", but maintains that nothing "explicit" was formulated and that Céline Sciamma "minimized things". "I come out of this discussion thinking that something serious happened between Christophe and Adele, but I don't put any sexual connotations to it. "On his way home, he told his wife about it, then said that he had later questioned Christophe Ruggia: "He told me to get lost, that yes, they had had a falling out, but that it was none of my business. I didn't look any further. "He said that he had "crossed paths with" Adèle Haenel several times afterwards, and noticed "her coldness" towards him, but that she no longer brought up the subject.

With regard to the facts brought to his attention, he assures that he was "stunned". "It was a difficult, intense shoot, there was a lot of fatigue, a lot of hours, and a 1.1 million franc hole in the budget [168,000 euros - editor's note]," he admits. But he says that "no one reported any problems with Christophe Ruggia" on the set, and that he himself, present "regularly" on the set and at the Yokohama and Marrakech festivals, had "not noticed anything that shocked him".

"I may be in unconscious denial, but for me there was zero ambiguity. He was very close to Adele and Vincent. They stayed together several years after the filming, I interpreted that as a director who is careful not to let the children down after the film, because it can be difficult to return to their normal life. "While he concedes that Ruggia's method of working with the children was "special", he explains that the director had "shot with a lot of children before", which inspired "confidence".

Eric Guichard, the cinematographer, was also adamant about why Adele Haenel "was ignoring Les Diables in the media. He said he got the answer "in 2009 or 2010" from "someone on the set". "I understood from this conversation that there had been some problems with Christophe, some touching after the shooting. »

For his part, actor Vincent Rottiers "wondered" about the breakdown of contact between Ruggia and the actress. "I didn't understand. I told myself that she had her career now." On 5 June 2014, during a preview of Adèle Haenel at the Forum des images in Paris, he explicitly questioned her. "I told him, 'Why did you leave? Did something serious happen, paedophilia? Tell me and we'll sort it out!" I wanted her to react, so I preached the fake so I'd know the truth. I didn't get my answer, she was silent," he explains. Three days later, the actress transcribed this conversation precisely in a new letter to Christophe Ruggia that was never sent, which Mediapart was able to consult. In it, she relates in detail the facts she denounces, using the words "paedophilia" and "abuse of someone in a situation of weakness".

There is sometimes a discrepancy between what Adèle Haenel believes she expressed and what her interlocutors understood. Over time at least, for those who were willing to listen, the actress did not hide from the media that Les Diables had been a painful ordeal. In 2010, in an interview devoted to the film, she insisted on the danger of the director's "control" "that brought you to the light, that brought you knowledge", his power to "shape an actor", all the more so "when he is small". They don't realize they're overstepping the boundaries of what they need to do in someone," she says. ... I'm not going to have that kind of thing happen to me anymore, because now I've been in that kind of relationship ... and then I went to school. "Two years later, she confides that she "couldn't watch the film anymore, it was too weird". In 2018, in Le Monde, she evokes a "traumatic" experience, "incandescent, crazy, so intense that afterwards I was ashamed of that moment". "We had to try to keep on living in order to build ourselves up," she adds.

When the #MeToo movement exploded in the fall of 2017, many of her family and friends "immediately" thought of Adèle Haenel. They wondered if the actress would take the plunge "to free herself from this story". "Maybe it's time," slipped Céline Sciamma. But the actress isn't ready. She also refused a year later, when she made the front page of Le Monde magazine. "The journalist asked me "What happened on Les Diables?" ", recalls Christel Baras. I called Adele: "Are you talking about it or not?" She said no. "I didn't know how to talk about it, and the fact that it was close to a pedophilia case made it even more complicated" the actress said today.

The first page of Christophe Ruggia's scenario "The Emergence of Butterflies" © Document Mediapart

The trigger will come in the spring of 2019. With the documentary devoted to Michael Jackson, but also by discovering that Christophe Ruggia was preparing a new film whose heroes bear the first names of those of the Devils. "It was really astonishing. This feeling of impunity... For me, it meant that he was completely denying my story. There comes a point when pretense is no longer tolerable," she says. The actress also fears that the acts she says she suffered will be repeated in this new film, entitled The Emergence of Butterflies, which features two teenagers.

The screenplay, which Mediapart obtained, does raise questions. It deals with domestic violence, "toxic relationships", harassment in high school, an affair between an adult and a minor, and "a case of rape of a minor". Like the director's other films, this feature film is "partially autobiographical, strongly inspired by his adolescence", according to the application for funding obtained by Mediapart.

Ruggia's note of intent describes characters from "real memories [that] mingle with memories that are told, fantasized, rearranged according to his unconscious, his fears or his anger. "First names were a wink, a tribute to the Devils," producer Bertrand Faivre told Mediapart. He says he "froze the project as a precautionary measure" in July, two weeks after learning of the existence of our investigation. He explains that he "will no longer work with Christophe Ruggia".

On September 18, on the occasion of the release of the film Portrait of the Young Girl on Fire, in which Adèle Haenel is starring, the director posted a photo of her from the film, along with a heart, on his Facebook account. Asked about the meaning of this publication, even though he had - according to his sister - knowledge of the actress's accusations, Christophe Ruggia did not answer, sticking to his overall denial.

Christophe Ruggia on his Facebook account on September 18, 2019, the day of the release of the film "Portrait of the Young Girl on Fire".

For Céline Sciamma, in this case, the asymmetry of the situation should have been a warning: "Christophe Ruggia has hidden nothing. He publicly declared his love to a child in social gatherings. Some people bought his score of the rejected lover, who was going to be pitied because he was heartbroken, that he had given everything to a young girl who was reaping averything from him. »

Adèle Haenel says she measures the "mad strength, the stubbornness" that it took for her, "as a child", to resist, "because it was permanent". "What saved me was that I felt it was wrong," she adds. The actress feels that her social ascension has been part of her success in breaking the silence. "Although it is difficult to fight the power balance that has been in place since her early teens and the gender domination, the social power balance has been reversed. I am socially powerful today, whereas he has only diminished," she says.

Adèle Haenel receiving her 2nd César (for best actress for her role in "Love at First Sight"), on 20 February 2015. Reuters

The actress sees her public speaking as a new "political commitment" after her coming out on the Caesar stage in 2014. "In my current situation - my material comfort, the certainty of work, my social status - I cannot accept silence. And if it has to stick to me all my life, if my film career has to end after that, too bad. My militant commitment is to take responsibility, to say, "There you go, I've been through this", and it's not because you're a victim that you have to bear the shame, that you have to accept the impunity of the executioners. We must show them the image of them that they do not want to see. »

If the actress speaks publicly today, she insists, "it is not to burn Christophe Ruggia" but to "put the world back in the right direction", "so that the executioners stop strutting around and face things", "that shame changes sides", "that this exploitation of children and women stops", "that there is no longer any possibility of double talk".

A statement shared by director Mona Achache, for whom it is not a question of "settling scores" or "lynching a man", but of "uncovering an abusive ancestral way of functioning in our society". "These acts stem from the premise that normality lies in the domination of men over women and that the creative process allows any extension of this principle of domination, up to abuse," she analyses.

Like her, Adèle Haenel also intends to support, through her testimony, the victims of sexual violence: "I want to tell them that they are right to feel bad, to think that it is not normal to suffer this, but that they are not alone, and that we can survive. We are not condemned to a double sentence. I don't want to take Xanax, I'm fine, I want to lift my head". "I'm not brave, I'm determined," she adds. "Talking is a way of saying you survive. »