What difference has throw-in coach Thomas Gronnemark really made to Liverpool?

Liverpool’s Champions League game against Midtjylland on Wednesday night will have no impact on the outcome of Group D, with Ajax’s match against Atalanta deciding who stays in the competition and who plays in the Europa League next February. It is, however, a match of importance to those who care about innovation within the game, especially when it comes to throw-ins.

The common thread running through Liverpool and Midtjylland is Thomas Gronnemark. A former sprinter and member of the Danish bobsleigh team, Gronnemark turned his attention to coaching throw-ins in 2004, with Liverpool and Midtjylland being the two most high-profile clubs with whom he has worked in recent seasons.

Gronnemark spent 10 seasons with Midtjylland, with 2019-20 being his last. His time with Liverpool is well documented. He joined the club in the summer of 2018 and is now into his third season.

Speaking to The Athletic, Gronnemark discusses how the focus of his coaching at both clubs has been slightly different, and some of the specifics when it comes to improving throw-ins.

“I categorise throw-ins into three categories — long, fast and clever. With Liverpool, I work more on the fast and clever options, as they don’t look to utilise the long throw into the box when in the final third. With Midtjylland, it was more focused on long throws.”

Those results marry up with the data too. In the four seasons from 2015-16 to 2018-19, Midtjylland scored 35 goals from long throws. Since joining Liverpool, the team has created just 10 shots from long throw-in situations across games in the Premier League and Champions League.

By defining all throw-ins that travel 20 metres or further as “long throws”, and looking at the data from this Premier League season, it’s also clear that Liverpool mix up their throw-in routines, not relying on the long option as much as Fulham, but not going short as often as Leeds United either.

Midtjylland are a team who have profited a lot from throw-ins in the past, but Gronnemark feels the team isn’t currently as dangerous from these situations.

“You always hear commentators say, ‘Midtjylland are a big threat from long throws’, but in truth, they’ve not been as good this season,” he continues. “They are throwing the ball 31 to 33 metres currently, which is OK, but not as far as previous seasons and not enough to be threatening from a long throw.”

That’s reflected in the numbers, too. In the five group stage games so far, Midtjylland have failed to create a single shot from a long throw.

Long throws and crosses have much in common: those that are high and looping are easier for defenders to head away, and those that are fast with a flat trajectory are easier to flick on and cause problems in the box. Look for that with Joel Andersson’s delivery on Wednesday.

And while looking to create chances from long throw-ins is the most obvious area that Gronnemark’s coaching can impact, it’s from regular throw-in situations that he thinks there’s the most low-hanging fruit for clubs.

“You see it all the time at the very top level. Players standing still and not moving to create space, throws going down the line straight into an aerial duel or not to feet.”

Gronnemark does help coach throwing distance — his work with Andy Robertson has increased the Scot’s throwing distance from 19 metres to 27 metres — but his biggest goal is to increase what he calls “throw-in intelligence” in the players he works with.

“It’s not about memorising a playbook. It’s about helping the players think and work through the solutions themselves.”

Gronnemark mentions the throw-in “superpowers” that players may possess — a good first touch, speed, smart movement — that can all combine to help a team get out of pressure from a throw-in.

And pressure is of the utmost importance when considering throw-ins. “I measure throw-ins under pressure only. A lot of the coaching matters far less when not under pressure,” says Gronnemark. “Pressure can either be in the form of man-marking, zonal pressure or the ‘grey zone’, where it’s a bit of both.”

His role with Liverpool, therefore, is to help improve success from throw-ins when under pressure. Defining “success” from a throw-in under pressure isn’t the most straightforward of tasks though.

“Sometimes you won’t be out of pressure after six or seven seconds, so you can’t use the time that the ball is retained after a throw-in as a measure of success. Equally, you can pass the ball five, six, seven times and still be in the zone of the pressure. That’s why, for me, the objective is to get the ball out of the pressure zone.”

Throwing the ball either into feet or into space are the two solutions to getting the ball out of this “pressure zone”, and explain to some extent why Liverpool actually seem to go long from throw-ins fairly routinely, despite long throws not being something they are known for.

Casually watch Liverpool’s throw-ins and you won’t necessarily see any details that differentiate them from other teams in these situations. Go looking for Gronnemark’s work though, and you’ll start to see it more and more.

A player will make a blindside run out of nowhere to receive a pass, another will take a couple of steps back after throwing the ball to make a better angle to receive again, or look to switch the ball out of pressure entirely to the other side of the pitch. Evidently, there’s more to throw-in coaching than just the throw itself.

You also learn about Gronnemark’s coaching through what you don’t see. Rarely will a player throw the ball to shin height or higher, with most throws easily controllable by a team-mate.

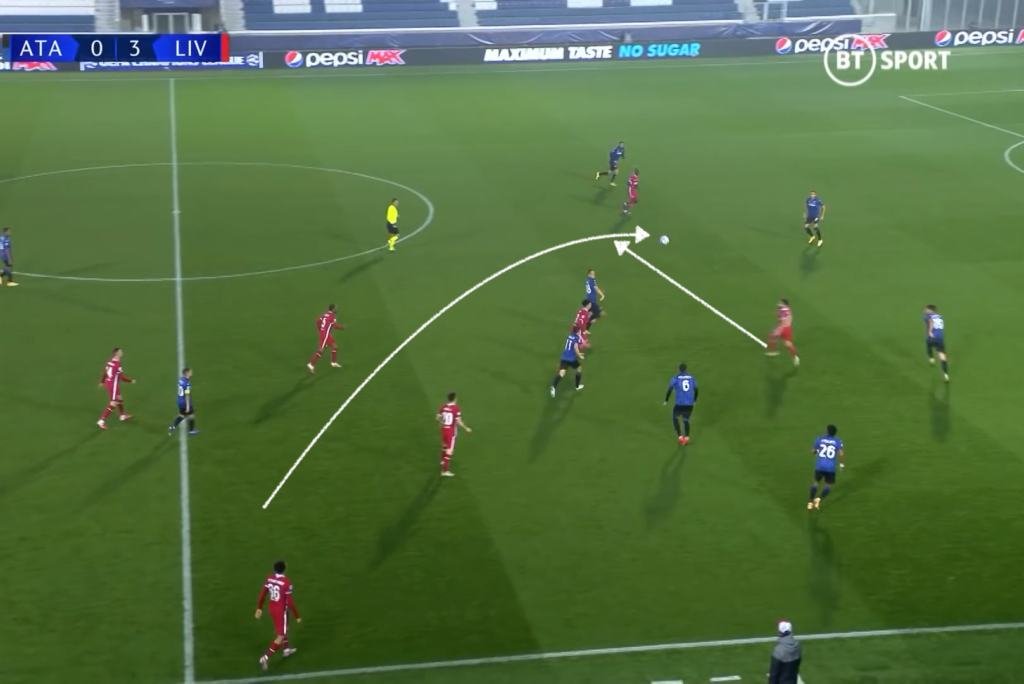

Practice was put into action against Atalanta earlier in the season, with Liverpool turning a throw-in on the halfway line under intense pressure into a goal just seven seconds later.

It all starts with Trent Alexander-Arnold, who has the ball in his hands against Atalanta’s aggressive man-marking schema.

After a couple of seconds, Liverpool start to move. Diogo Jota and Georginio Wijnaldum are drawn slowly towards the ball, and Curtis Jones makes a move upfield.

Off-camera in the previous stills, Mohamed Salah has darted infield to collect the ball in a pocket of space. There’s an element of luck in the way he beats Mario Pasalic to the ball…

…but he does, running into space…

…and threading an inch-perfect through ball for Sadio Mane to run on to, who ends up in the box and chips the keeper.

When discussing some of the data analysis prepared for this piece with Gronnemark, he was clear that not all throw-ins should be treated equally.

“Analysing success from throw-ins is so dependant on the context of the situation,” he says. “Are you by the opposition box or in your own half? What’s the score? Are you willing to lose possession in order to take a chance rather than be safe with it?”

Nevertheless, Liverpool’s share of “wasted” throw-ins — those which lead to the ball being retained for less than five seconds, with the opposition retaining possession afterwards — is the third-lowest in the league.

Throwing into space or to feet, moving to create an option for a team-mate, not throwing the ball down the line: if a lot of this sounds like common sense, that’s because it is. In football though, common sense isn’t always common practice.

“Coaches expect their players to be able to retain the ball from a throw-in without spending time on it in training,” says Gronnemark. “They throw their arms up in the air and get frustrated when they give it away easily, but don’t dedicate any time to improving them. Coaches are lacking the knowledge of what to do in these situations.

“I was working with Brentford in 2016-17 and 2017-18. They were only interested in long throw-ins. I can’t say a bad word about the coaching staff or the people, all were great to work with, but I was frustrated to not have the chance to work with the coaches on throw-in retention.”

Relieving that frustration is seemingly Gronnemark’s long-term objective, as the Dane is currently writing a book to help impart his knowledge of throw-ins across all levels of football.

“I’ve won the Champions League and the Premier League as Liverpool’s throw-in coach, but my biggest dream is to change football. I want to help those playing at amateur or youth levels develop this part of their game, not just those at the top.”

Perhaps the first copy could go to Hector Bellerin, who’s committed five foul throws already this season.

44

44