The unravelling of Sunderland How a Premier League club fell apart

Other contributors: Oliver Kay, Matt Slater, Laurie Whitwell, Dominic Fifield, Stuart James, Steve Madeley and James Horncastle

Sam Allardyce ripped aside his jacket and beat his chest like King Kong. 46,000 inside the Stadium of Light roared their approval. Sunderland’s players danced along during a lap of honour. They had just beaten Everton 3-0 to stay in the Premier League for a 10th consecutive season and their victory helped to relegate neighbours Newcastle United. There was joy on Wearside and a surge of optimism.

Had the Netflix cameras been rolling, they would have captured a champagne dressing room, where owner Ellis Short joined the revelry; the next day, they would have caught Penshaw Monument lit up in red and white by Sunderland City Council.

“It’s hard to beat that feeling,” Allardyce tells The Athletic. “I’ve won promotions with different clubs and it’s special but so is the feeling you get when you and your staff have managed to save a club. It’s relief but it’s also satisfaction. You know how much it means to Sunderland fans and everyone at the club. You could sense the relief.”

#OnThisDay in 2016...

Sam Allardyce celebrated with the Sunderland fans as the Black Cats narrowly survived from relegated

The club and its wider fanbase felt it was a moment of opportunity. Allardyce had only been there for eight months and he sensed it, too. It was May 2016 and it felt like Sunderland had bottomed out. The club had been teetering on the brink of relegation for seasons and had become known for acts of dramatic escapology.

But Allardyce, Sunderland’s eighth permanent manager in seven erratic years, had taken a sluggish squad that scraped 12 points from the first half of the 2015-16 season — and looked certainties to go down — and galvanised them into a streamlined team.

Jan Kirchhoff had arrived in January from Bayern Munich and had made a huge impact. “We all felt like we’d created something we could build upon,” he tells The Athletic. “That we were able to stay in the Premier League, perform in it, and might even be able to attack the top-10 teams. All of us felt like we had a great future.”

In the second half of that season, Sunderland’s record was P19 W6 D9 L4. Three of those defeats were to clubs in the top four. Against Everton, Allardyce named the same starting XI for the seventh game in a row. The previous match had been a stirring 3-2 victory over Chelsea. At last, Sunderland had a solid foundation.

Allardyce felt three high-calibre signings that summer would turn them into a team that could look forwards with optimism, rather than with the familiar sense of dread or confusion. “We have to move away from the fact that we’re all so happy at being heroes for surviving,” he said the next day. “We have to think much bigger, have much more ambition.”

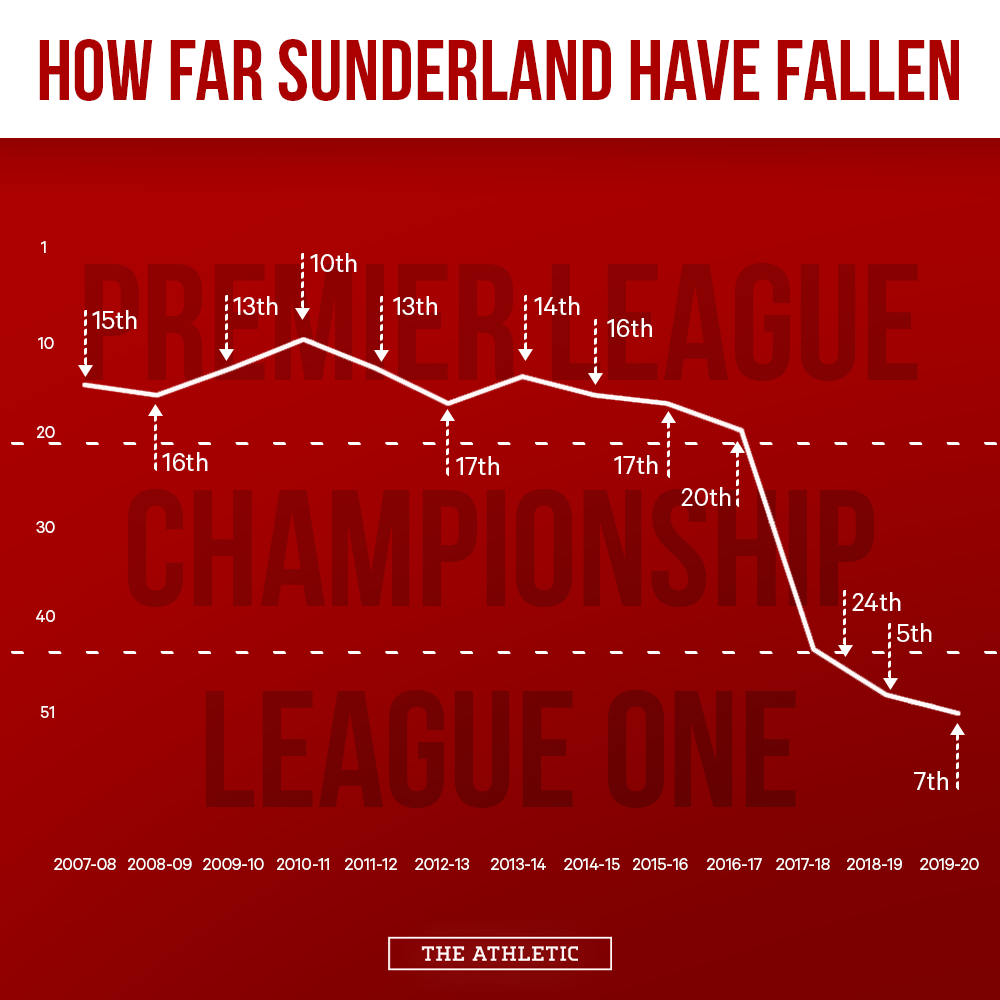

And yet, within two years, Sunderland were in League One. Back-to-back relegations ripped the heart and soul out of the club, much of it caught on camera in Neflix’s Sunderland ‘Til I Die.

No one foresaw that on the night of Sunderland 3-0 Everton. Then, “Sunderland ‘Til I Die” was still a chant, an expression of pride, rather than a soundtrack to decline. Then, Sunderland were still a big football club with possibilities, rather than a box set. It had provided a glimpse of the club it could be.

This was only four years ago this month. Even three years ago, Sunderland were still in the richest league in the world. Today, they feel like a Premier League memory.

Sunderland stand uncertain in seventh place in the third tier and, if the season ends now, it will be the lowest finishing position in their 141-year history. Today, talk is not about potential, about “a great future” — it is about flawed ownership, creditors, parachute payments, loans and regression. Talk is about Sunderland unravelling. It is about Sunderland dying. Nobody is dancing.

When Stewart Donald and Charlie Methven took control of Sunderland in the summer of 2018, they declared the “piss-taking party” was over. Short had sold up and, after all those years of mismanagement, there was a final act of benevolence; “Ellis has tidied up his debt and that’s now gone,” Donald, the chairman, said.

There remain questions about the tidiness of Short’s departure, just as there were questions then about whether Donald, an insurance specialist and former owner of non-League Eastleigh, had the money to take the club forward. Those were laughed off. “I know I’m supposedly worth £8 million but, somehow, I’ve managed to find £50 million in my piggy bank and the EFL have seen that,” said Donald.

“What can Sunderland achieve?” Methven asked. “The answer is the sky is the limit.” He referenced Borussia Dortmund, from “a big, serious working-class area, passionate about their football club” with big crowds and who “invest in their academy very, very heavily”. This, he said, “is the model for Sunderland”.

For a little while, fans laughed along, re-engaging as their new owners took to podcasts and Twitter to discuss their vision, to answer queries. Supporters were encouraged to come to the stadium to help replace sun-bleached pink seats; a crimson glasnost, all in it together.

Jack Ross, the young manager lured from St Mirren, inherited 10 first-team players and a blank canvas. The team lost one of their opening 20 league matches and suddenly, League One did not feel too bad; Sunderland were winning. But at the end of a season in which they sold Josh Maja, their leading goalscorer in January, Sunderland lost — in the play-off final. They were no longer on loan to a lower division.

Last spring, Sunderland were almost sold to Mark Campbell, a businessman. The process reached such an advanced point that Ross was being consulted by the prospective new owners.

“It was astonishing,” a senior club source tells The Athletic. “Jack was on holiday, getting messages about signings from the new people. He had to ask Stewart whether he was OK to talk to them. ‘Yeah, yeah, crack on’ he was told.

“There would be all these mixed signals. Jack would hear from the current owners that they were going to offer a certain player a contract. Why? Couldn’t they sell the club after all? Then Jack would hear again from the new guys — they would be at the club, inside the training ground, going for dinner with him, as if they had already bought it.

“Through the summer, we had no idea who was going to own the club. And then it just disappeared. Honestly, it was mental.”

In terms of infrastructure, Sunderland still thought of itself as a Premier League outfit. But a broken lift at the training ground was not fixed and behind the scenes, Donald and Methven were chopping a “ruinously high” £40 million wage bill down to £15 million.

“They were people who genuinely wanted to do a good job but I’m not too sure they knew how to do it,” another source at the club says. “On recruitment, it was fucking horrendous. They were so far out of their depth. I don’t think the chairman realised what a big job it was and didn’t really have the funds to do it. They were always chasing.”

On October 8, Ross was sacked. Sunderland were sixth in League One and, according to Donald, “the best chance of promotion is to change it”.

Two months earlier, he had said he was “close” to securing investment which would “take the club to the next level” but the enticing prospect of a takeover by a company which manages the assets of Michael Dell, currently ranked by Forbes as the 27th richest person in the world with an estimated wealth of about £23 billion, did not materialise. It became a £9 million private loan by FPP, associates of Dell’s, secured against Sunderland’s assets.

And then, there is Juan Sartori, the Uruguayan businessman and politician who had taken a 20 per cent stake in the club in order, said Donald, to “help us maximise Sunderland’s potential”. That stake cost Sartori £1. “We never knew what he did or why he was involved,” another source says. “He disappeared for months.”

Sartori and Methven pose with a Sunderland supporter in August 2018 (Photo: Ian Horrocks/Sunderland AFC via Getty Images)

On the pitch, Sunderland faltered under Phil Parkinson, Ross’s replacement, and then rallied, but they failed to win any of their last four matches before lockdown. Their best chance was not enough.

Off it, they remain in limbo, still “for sale and there are people interested” according to Donald, who describes himself as a reluctant seller. It has emerged that Donald effectively used Sunderland’s parachute payments as collateral to pay Short’s price for the club.

“On the face of it, Sunderland should be an easy sell,” one person involved in a consortium which attempted to buy the club last year, tells The Athletic. “They’ve got the stadium, the fanbase and a good academy but behind the scenes, it’s a mess. For the money they’re asking, you could buy a Championship club, with fewer nasty issues.”

Between them, Sunderland’s under-18 and under-23 teams have a record this season of P34 W0 L 33 and a goal difference of -99. Donald has permanently deleted his Twitter account. Methven stepped down as a director in December for “personal reasons”; he had also been recorded saying Sunderland fans “are unbelievably uneducated in business terms”, though he has since said he regrets his “off-the-cuff” remarks.

If the finances were not opaque, they might be easier to read. This is what is deterring at least one interested party, wondering like so many, how a club that received £890 million in TV payments in the Premier League could be so skint and whether, as Methven said last August, they are still paying £50,000 a week to players no longer at the club.

“The owner would make a plan — one year, three years, five years — and then as soon as you lose four games, the plan’s gone. That’s where the club was at. We could never build.”

This is Lee Cattermole speaking to The Athletic earlier this season about Sunderland. Cattermole moved to VVV Venlo in the Netherlands after a decade on Wearside, where, beginning with Steve Bruce, he worked under 10 permanent managers plus three stand-ins.

“There were always new beliefs,” Cattermole says. “I’ve tried to follow every manager. You go again, you get some hope back — ‘this is what we’re going to do’ — and then ‘for fuck’s sake; it’s happened again’. You were constantly building relationships. Brucie knew I’m a decent lad, good to have in the dressing room, but maybe the next manager comes in and thinks: ‘This guy is causing havoc’. You lose your stability as a player.”

In December 2008, Roy Keane became the first of Short’s ex-managers. Ricky Sbragia soon followed. Then came Bruce: over £30 million was spent in the summer of 2009 on Darren Bent, Lorik Cana and Cattermole, and they finished 13th. The next season, it was 10th but Bent had been sold and there was an air of anti-climax.

It was November 2011 when Bruce was dismissed and the incessant churn that would dominate Short’s regime was under way. A club was being constructed on quicksand.

Bruce’s replacement was Martin O’Neill. O’Neill spoke of Barcelona and wondered if he could build a team who could “play like that”. Results turned and then turned again. Adam Johnson cost £12 million but behind the scenes, it felt like something had broken.

Niall Quinn, the former hero-striker turned chairman, provided glue, an emotional link throughout the club; he departed three months after O’Neill’s appointment, his “magic carpet ride” over. Quinn’s football nous was missed when matters turned sour.

And they had turned sour. “It was chaotic, dysfunctional,” one former insider tells The Athletic. “Sunderland had no strategy. It was all ‘Stay up, stay up. Patch it up, patch it up’. They paid good salaries but it was all short-term solutions.”

O’Neill was the next to go when Short again feared relegation. It led to his wildest appointments — Paolo Di Canio as head coach and Roberto De Fanti, the Italian agent, as director of football. When Sunderland won 3-0 at Newcastle in Di Canio’s second game, he literally slid down the touchline into many fans’ affections.

Di Canio celebrates on his knees. Sunderland’s slide was yet to come (Photo: Owen Humphreys/PA Images via Getty Images)

“Ellis asked me to suggest a manager who could provide an electric shock at short notice,” De Fanti would later say. Short had come to rely on these sharp shocks.

Thirteen players came in that summer, including Jozy Altidore from AZ Alkmaar, but Sunderland won none of their first five games. Senior players, such as John O’Shea and Cattermole, expressed serious concerns about the Italian’s intense, unconventional methodology to Margaret Byrne, the chief executive, and Di Canio was out.

Attendances were good but the club was handing out free tickets in thousands, not hundreds, and Short was now onto his sixth manager. Gus Poyet’s first game was a 4-0 defeat at Swansea which left Sunderland bottom with a single point. Their next opponents were Newcastle. Fabio Borini, who had arrived on loan from Liverpool, scored a late winner.

“Gus was changing things,” Cattermole says. “I don’t like the word ‘identity’ but we were playing in a different way, holding the ball.”

A run in the League Cup had begun. It would take Sunderland to Wembley. David Moyes’ Manchester United were beaten in the two-legged semi-final. In a penalty shoot-out in front of 9,000 travelling fans at Old Trafford, goalkeeper Vito Mannone saw the Wearsiders through. It was arguably the best night of the Short years.

They lost to Manchester City in the final, then won none of their next seven league games. With five matches left, Sunderland were bottom, six points from safety. “There is something wrong at the football club,” Poyet said memorably — without naming names. Stories appeared about the club’s “rotten core”.

But then came Poyet’s “miracles” — four consecutive wins and, again, Sunderland had stayed up.

“Every feeling possible was in that season,” Borini tells The Athletic. “It was frustration, lows. It was excitement. But it was also fighting back from a position that meant death (in football terms). We were dead in January and then I don’t know how we resurrected from death. That year, I found Sunderland at its best because I could feel the work ethic and the desire. We could feel the club was still there, it was still big.

“It’s one of those crazy, up and down, emotional clubs.”

Ellis Short IV, to give him his full name, took full control of Sunderland in 2009, having purchased 30 per cent from Quinn’s Irish Drumaville consortium a year earlier. It cost him over £20 million, plus £40 million of debt the Irish had inherited.

Short was a 48-year-old American who spent much of the previous decade in Japan. His Lone Star Investment Fund specialised in “distressed assets” and it was a lucrative business. Short owned an estate in Hawaii, a mansion in London, a castle in Scotland where Madonna married Guy Ritchie and now a Premier League club.

There was no mission statement or introductory interview, Short was simply the new man in charge — though subsequently, he has given a lengthy interview to Sunderland ‘Til I Die. Curiously, it was unused.

What we do know is that Short can be demanding and impulsive. An imposing figure, basketball-tall and self-assured, Short’s patience was like his surname. Keane was the first of his Sunderland managers to discover this — Keane says Short spoke to him “like I was something on the bottom of his shoe” — and nine years later, Simon Grayson was effectively sacked in the tunnel post-match. Short did not even speak to Grayson’s successor, Chris Coleman.

It was no way to run a football club. What Short did, however, was cover Sunderland’s losses. Each financial year, it was £15-30 million and over a decade, that adds up. It is why supporters never turned on the billionaire despite the obvious absence of strategy.

There were some good moments on the pitch — 10th place, a cup final — plus there were other benefits. Short’s wife Eve Zimmerman is a former tennis player and when Short took Martina Navratilova as his guest to a Fulham game, it was to see his Premier League club. The same occurred with other guests at other grounds. Ownership brought a certain Saturday status.

And Short was stimulated by Sunderland. At the Academy of Light for youth-team games, he was approachable. He could be generous, promising the squad a paid-for trip to Las Vegas if they won a particular game at Portsmouth — they lost; there was the tale of his £1,000 tip at a Seaburn curry house. He enjoyed a bit of local limelight.

Short and David Miliband, who would later resign from the club’s board (Photo by Michael Regan/Getty Images)

His son, Ellis Short V, was regularly a match-day mascot. He is now a budding tennis player in America.

Another son — not Short’s — was Ryan Sachs, whose surname relates to Goldman-Sachs. Although it was never trumpeted, Sachs, someone people inside the club thought was there for work experience at first, became “Football Operations Director”. Sachs spent three years in the post. How qualified he was for this senior position is unclear.

Who was going to challenge Short? Byrne, the CEO, was young and like Short, had no strong background in football.

In 2013, they appointed Di Canio as manager. If one accusation is that Short kept steering Sunderland into ditches, here was a question about Sunderland’s moral compass. Di Canio’s dedication to historical Italian Fascism was at the very least going to trouble the County Durham miners whose banner adorned the reception stairs at the Stadium of Light.

The stadium was built on the site of the old Monkwearmouth colliery and the “Light” in its name referred to miners’ lamps. These were Labour Party people unlikely to welcome Di Canio’s views. They didn’t. David Miliband, the Labour MP for South Shields and former UK Foreign Secretary, was on the club’s board. He resigned.

But Short ploughed on with Di Canio — until results worsened.

Another moral question arose in 2015 when Adam Johnson was arrested and charged with sexual activity with a 15-year-old girl. The club suspended Johnson, then allowed him to play again while the trial was pending. He scored crucial goals; his presence made many uncomfortable. Eventually, Johnson pleaded guilty to two charges and was sentenced to six years in jail.

“The way the club handled the case was a disgrace,” a former insider says. “It was horrendous.”

“We made a lot of mistakes,” another senior figure says, which is an understatement.

Byrne resigned — receiving an £850,000 pay-off — and took the blame for the damage done to Sunderland’s reputation. But many inside Black Cat House, the club’s offices, suspected Byrne had been obeying Short’s instructions.

Di Canio and Johnson were two of the reasons why, in one of his occasional programme notes, Short described periods of his tenure as “gruelling” but he emphatically rejected the accusation that he was penny-pinching. Sometimes, a fan or former player such as Michael Gray would make such a comment.

Short’s response was: “I have never taken money out of the club. In fact, I have funded significant shortfalls each and every season. The amount that I fund, every season, exceeds the collective total amount funded by every owner the club has ever had since the club was formed in 1879.”

There was more but Short ended with: “The bad news is, for that amount of money spent, we should be better than we are and no one knows that more than me.”

After Poyet’s miracle, it seemed Sunderland had begun to reorganise but it was wishful thinking. De Fanti was gone, replaced by a sporting director, Lee Congerton.

“We want a British heart to Sunderland’s team, with a Spanish way of playing,” Congerton said.

Jack Rodwell was bought from City for £10 million that summer. He was on £73,000 per week. He scored on his home debut. Another signing, on loan, was Ricky Alvarez, whose cost would multiply in a later, lost arbitration cases.

“I always got the impression they had this inferiority complex — ‘people don’t want to come here, so we’re going to have to get who we can and pay well’,” an agent who did business with the club at the time says. “So when it came to recruitment, I found they were… not desperate but didn’t have a proper plan. It went from one regime to another, all suffering from previous mistakes.”

The climate inside the club was difficult. “You were working with your hands tied behind your back,” one insider says. “Sunderland was a Premier League club only in name. It was like you’d look under a bit of paper and go, ‘Oh my God’, and push it back down. Every day was firefighting.”

Season 2014-15 brought another slow start, no league win until October and Poyet’s time was over when his team were 4-0 down at home to Aston Villa in March. He was dismissed 48 hours later as another short-term plaster was sought. It came in the unlikely form of 67-year-old Dick Advocaat.

It was another voice, another style for the players, but again — in the short-term — it had the desired effect. In Advocaat’s second game, Jermain Defoe smacked in an unforgettable volley to defeat Newcastle and when Sunderland drew 0-0 at Arsenal in the penultimate match, they were safe again. It was the third late escape in a row. Advocaat, “The Little General”, was in tears.

He wanted to leave. Offered a reported £4 million-per-annum contract — and with fans sending flowers to his wife — Advocaat stayed and set about recruitment. He wanted to buy Adrian Ramos from Dortmund; he got Ola Toivonen on loan from Rennes. And after eight games produced three points, for the sixth time in seven years, Sunderland changed manager mid-season.

Next was Allardyce and there was no mention of magic carpets or Barcelona. “I’m here to save them,” Allardyce said. “I’m the troubleshooter.”

Safety was secured, Allardyce left for England and Moyes, described by Short as his “number one managerial target for the last five appointments” arrived. “This is firefighting,” he said as Sunderland set off for pre-season in France. The flight was re-routed to Manchester airport due to a fault with the plane. “With hindsight, you can say it was an omen,” Jan Kirchhoff says. “We were just happy to arrive safe.”

Kirchhoff, a composed, defensive midfielder, had been signed from Bayern Munich’s reserves in Allardyce’s January, along with Lamine Kone from Lorient and Wahbi Khazri from Bordeaux.

Eight months later, the mood had morphed. A permanent move for Yann M’Vila, the France international, and a midfielder to construct a team around, did not happen. Younes Kaboul, “a leader for us,” Kirchhoff says, was sold to Watford. DeAndre Yedlin returned to his parent club, Tottenham Hotspur.

“The players who had been there weren’t unhappy,” says Kirchhoff, “but we could see the quality wasn’t as high as the season before.

“Personally, I never re-found my self-confidence. My position changed, my team-mates changed around me and it didn’t feel like it was before. It wasn’t any one specific fault. Football is like a big puzzle and the pieces have to fit.”

After Sunderland 3-0 Everton in May, Kirchhoff’s next Premier League game was Sunderland 0-3 Everton in September. Sunderland had 33 per cent possession. There was none of the “energy and power” Kirchhoff had noted before.

“I don’t know if I can say this,” he says, “but I just felt helpless, like there’s no chance we can win this, tactics-wise, physically, on the ball, off the ball.”

It was the third of eight losses in Sunderland’s opening 10 league games. This was not Allardyce’s flying start. Sunderland were going down.

Moyes had said as much after the first home game against Middlesbrough, a 2-1 defeat. Kirchhoff is adamant that the players were giving everything but the message from Moyes was dispiriting.

“The surroundings around the club turned quite negative,” Kirchhoff says. “Our manager said quite early on in the season that it was going to be hard for us to stay in the league. It felt like a self-fulfilling prophecy.”

Long before official confirmation arrived — following a 1-0 home defeat to Bournemouth in April 2017 — Sunderland accepted relegation.

“I think the fans felt the same,” Kirchhoff adds. “We’d all been waiting for the moment. It wasn’t one game that broke our neck.

“In the dressing room, heads were down. I remember people almost crying, staring. It’s hard. You don’t know what to do. It was the worst case for Premier League footballers. Other things come in, too. You know people will lose their jobs at the club. You just want to get away from it.”

Sunderland had won one league game between Boxing Day and relegation day, one win in four months. In the last 13 games of that run, Sunderland failed to score in 11. There was a squad bonding trip to New York as cleaners were being made redundant on Wearside. The club had fractured. Sunderland finished bottom.

Kirchhoff, among others, was leaving. “I’d made the decision earlier: I don’t want to work under these circumstances, with this manager. I felt like it was over; not the place for me, I just didn’t feel well. It wasn’t right, the way we played football. I didn’t get on with David Moyes. The system he wanted to play, I didn’t understand really. I didn’t understand his views of football and he didn’t understand mine.”

Kirchhoff was a key player under Allardyce but did not share Moyes’ views of the game (Photo: Ian Horrocks/Sunderland AFC via Getty Images)

Moyes’s four-year contract lasted 10 months. It was not all his fault. The sale of Patrick van Aanholt to Crystal Palace in January meant another member of the Allardyce back four was gone. The club held on to Kone when Everton offered £16 million but committed to paying him a staggering £90,000 a week — for five years. Papy Djilobodji cost Chelsea £2.7 million; he made one two-minute appearance for them, then cost Sunderland £8 million.

“Some of the things I heard… wow,” a member of the coaching staff under a later manager, says. “Some of the agents’ fees they were paying out were unbelievable and they had so many average players on fifty grand a week.”

Grayson was appointed as a Championship specialist. He lasted 18 games; the team were third-bottom and by now, the Netflix cameras were trained on them. Some of the glare was unforgiving.

“I didn’t have any choice in the matter,” Grayson tells The Athletic of Sunderland ‘Til I Die. “Moysey said they’d tried the year before and he’d stopped it but they’d already agreed to it when I arrived. It’s edited in a certain way. We were scoring goals at Norwich and there I am celebrating in front of red seats at the Stadium of Light.”

Costs had been slashed by Martin Bain, Byrne’s successor as chief executive. Another 70 people left the club, the women’s team became part-time. Short was nowhere to be seen.

Bain turned to Coleman who, in his previous job, took Wales to the semi-finals of the European Championship. Sunderland’s stature and potential, “really turned me on,” he tells The Athletic. “I was like: ‘I’ll get my teeth into that one’. You think you can turn it round.”

He could not. when Sunderland beat Fulham 1-0 on December 16, 2017, it was their first victory at home for 364 days.

“I never had one conversation with the owner. Not one phone call or text message,” Coleman says. “Nothing. No contact. I said to Martin, ‘Look, I’ve got to make contact with the chairman’. Martin tried, and I got ‘No, not interested.’ I said, ‘Look, we’re going to get relegated’. ‘Nope’.

“It needed a mass clear-out, a complete change of direction. It needed a chairman who was going to be there for a while. Not the one we had, who lived in America and had no interest in the club other than ‘How quickly can I get it off my hands?’.”

Coleman’s warnings were unheeded and Sunderland slumped into League One. Recruitment had failed again. Of dozens of signings in 10 years, only four players were sold for profit and of Short’s 11 managers, only Bruce spent more than two years in post.

“It’s just such waste. That’s the overriding feeling,” says Chris Weatherspoon, a fan, accountant and the author of Short-Changed. “It’s kind of a blueprint in how not to do it.”

Looking back, Allardyce tries to comprehend the unravelling of Sunderland. He thinks of May 11, 2016 and wonders how from a position of promise, the club has got it so wrong.

Fault lines were evident, though, and not only with hindsight. “It had been a continuous struggle,” he says, “that constant battle to establish yourself in the Premier League. You look at the managers Sunderland had in the Premier League, including very experienced people like Steve Bruce, Martin O’Neill, Dick Advocaat, myself, David Moyes, and all of us found it a struggle to some extent. Struggling became the norm. And that can’t be down to the manager every time.”

Allardyce met Short a week after survival. He felt another three signings of the calibre of Kirchoff, Kone and Khazri were required.

“I was trying to explain what needed to be done to make sure we’re not in the same position again the next season,” he says. “Let’s break that mould. But it was going to cost a considerable amount of money.”

Short’s concern was less about the £15 million spent in January, then the number of unwanted players still on the wage bill and, significantly, the amounts owed on previous transfers. Accounts to July 2016 showed £35 million was outstanding.

“Ellis was excited by staying up again,” Allardyce says. “But I think the difficulty was when it came to planning and trying to do the things where we could say: ‘Let’s stop this happening again’. He had to look at the budget and all the costs involved and I think he was probably thinking: ‘So it’s going to come down to me again, is it?’ and I can understand that. I had some sympathy with Ellis.

“I wonder if it was a mistake for Ellis to let Quinny go when he restructured the club. A few people suggested that to me.”

Why does he think Short bought Sunderland?

“He lived in London and I think he enjoyed owning a Premier League club,” Allardyce says. “He got a bargain and I think he got the bug. He spent a lot of money early on. Then, over time, I think he probably lost the bug because of the situation year in, year out. No matter how much money you’ve got, if you’re the one that has to keep putting millions in, that must grind you down.”

While Allardyce was getting the chemistry in the dressing room right, there were occasions when he felt isolated, such as during the Johnson fallout, but by the end of his half-season, Allardyce thought: “We’d a really good spirit in the dressing room between players, staff and myself. That’s one of the reasons why we stayed up. The fans were brilliant. They bought into it as well. We were a struggling team and we were still getting 43,000 every week. That’s some going, that.”

Kirchhoff says the same: “The whole club and the team were really positive. The manager gave us great self-confidence. We always felt like we had the quality to stay in the league — the performance against Everton typified that. We performed at a high level against a good team, we dominated them.”

Kirchhoff was 26, had experienced Jurgen Klopp as a youth-team player at Mainz and Pep Guardiola as a first-team squad member at Bayern. He was impressed with Allardyce and with the club.

“Oh, absolutely,” he says when asked if the environment felt healthy and professional. “The standard at this time was really high. I wouldn’t say it was Bayern Munich, but it was amazing.”

Kirchhoff’s impressions of that Everton night four years ago confirm what many observers thought — this was different to previous Sunderland escapes. This was a chance to change and grow.

“To be fair, I have lots of memories like this of Sunderland, occasions with lots of energy and power. That Everton game was one of them. Ellis Short came down to the dressing room to congratulate us all. He had a drink with us, thanked us. Sam was happy. This is what I experienced of the club — really familiar, friendly, all the staff members were in the locker room, the lady who took care of travel. They were all there to enjoy it. I felt welcome and part of a great club.

“I personally felt the best in that half-year under Sam, so I have really strong feelings for the club. I hope it somehow brings back its energy.

“Today? I feel sorry almost. I don’t know if that’s the right word.”

Given Sunderland’s historic low, its tense present and uneasy future, as it drifts to the margins of English football, sorry might not be hard enough.

(Photo: Ian Horrocks/Sunderland AFC via Getty Images)