Global debt: Why has it hit an all-time high? And how worried should we be about it?

Global debt hit an all-time high of $233 trillion (£169 trillion) in the third quarter of 2017, according to the Institute of International Finance (IIF).

That’s a $16 trillion increase on debt levels at the end of 2016 and more than three times the size of the global economy.

Who has all this debt? Who is it owed to? What does this level of indebtedness mean? And how worried should we be about it?

Who has this debt?

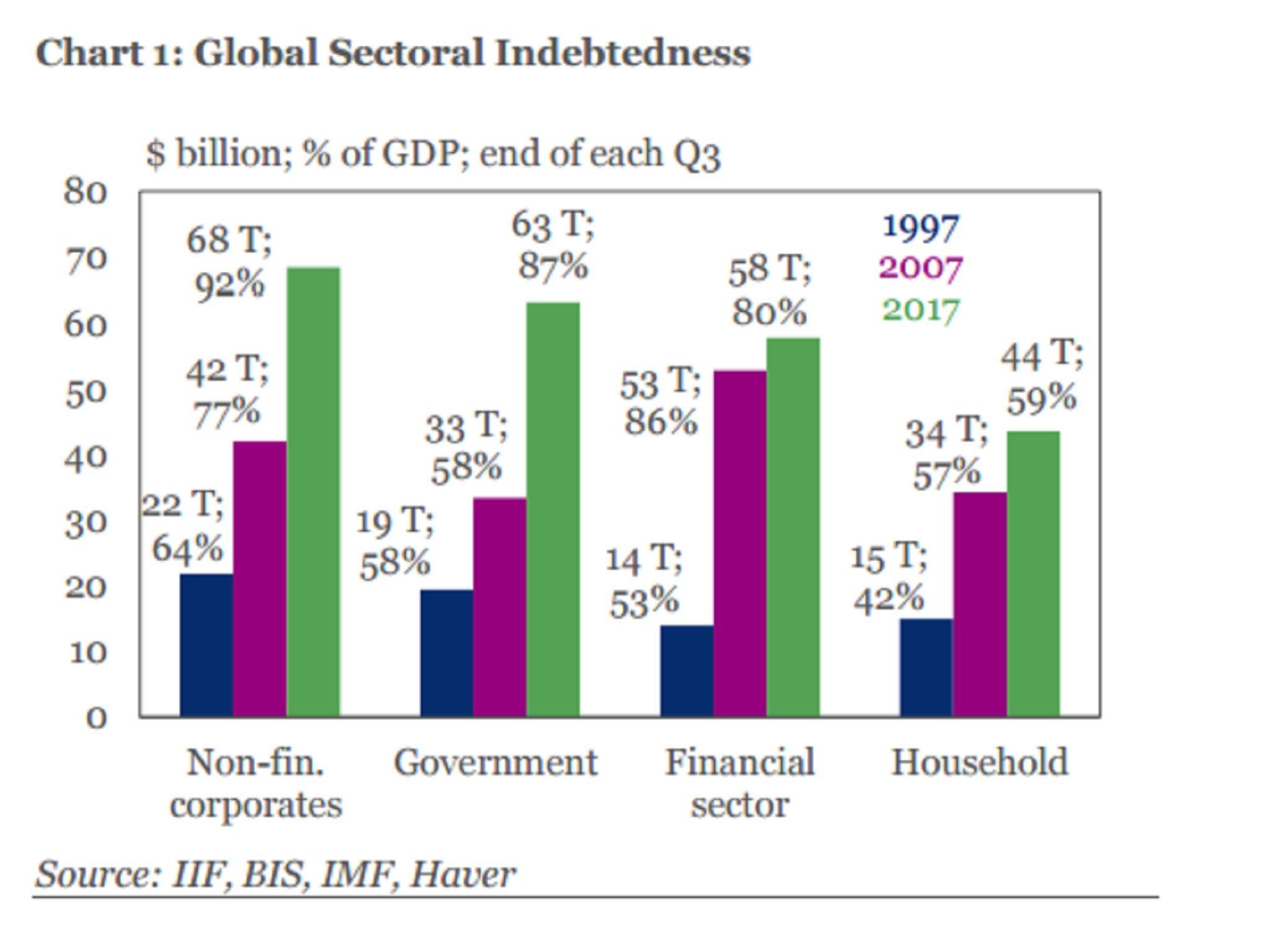

According to the IIF, $68 trillion, the largest chunk, belongs to non-financial companies.

The next biggest borrowers are governments around the world, which have $63 trillion in debt. Financial institutions have $58 trillion of borrowings.

Finally there are households, with total debt of $44 trillion.

And who is this money owed to?

“Us” is the short answer. Every financial liability, which includes debt, has a corresponding financial asset. And all those financial assets are ultimately owned by someone.

If you put your money in a bank account the bank is likely to loan the cash out to someone else to buy a house: your financial asset thus becomes someone else’s financial liability.

Debt is a form of wealth.

So it doesn’t matter that global debt is growing because it also means global wealth is rising?

Up to a point.

The economic function of debt is to allow economic actors to spend more today than their incomes would otherwise allow.

Households and firms borrow in order to finance consumption or investment. This can be a good idea if their income is temporarily restrained and spending more today will increase their welfare.

If the money borrowed is used to expand the future productive capacity of that economic agent – for example by spending it on education or increasing a firm’s capacity – taking on debt can be also be a very wise move.

Some of the world’s major religions revile money lending, but, economically-speaking, debt is not an inherent evil.

Only the best news in your inbox

The problem comes when the debt taken is excessive and the interest or scheduled repayments potentially cannot be serviced, risking bankruptcy for the borrower and a sudden loss of wealth for the lender.

It’s also a problem when the money raised by debt is unwisely invested.

What about governments?

This is a special case because governments, generally, can raise money through taxation and thus effectively control their own income. They also often borrow money in a currency they themselves print, meaning that, in extremis, they can ensure lenders are paid back by printing money.

The fact that governments also do not have a fixed lifespan, unlike individuals, means they can generally roll over their debts indefinitely.

This all enables many governments to borrow on considerably easier terms than households and most companies.

Governments, it is true, can still overborrow and run into a funding crisis. One often sees this with developing world states run by chaotic and corrupt administrations.

We also saw it with Greece in 2010. But it’s important to note that Greece was unusual among high-income nations in that it was not borrowing in a currency (the euro) that it printed itself.

States also have a role in macroeconomic stabilisation in times of recession. When governments fail to increase their borrowing and spending to support overall demand that can be a damaging false economy for the government itself and also the wider economy.

Government underborrowing can be as big a problem as overborrowing.

So is global debt excessive today?

Some argue so. A group of economists in 2014 warned that rising global debt (or “leverage”) was risky and could be hindering the international recovery.

The IIF warns that if interest rates rise around the world that could make many debt burdens harder to service.

The former chair of the Financial Services Authority, Adair Turner, wrote a powerful book in 2015, highlighting the apparent reliance of many economies on ever-growing debt piles, generated by unstable financial systems, to drive decent GDP growth.

There’s a strong argument that giant banks in developed countries still fund their balance sheets with too much debt, rather than equity capital, running the danger of a repeat of the 2008 global financial meltdown.

However, the IIF also points out that, despite hitting a new high in nominal terms, the share of global debt to global GDP has been falling for four consecutive quarters.

This is because global GDP has been picking up fairly robustly. The fact that incomes are now rising faster than debts should make the borrowing burdens easier to service, even if interest rates do creep up.

So nothing to worry about then?

It may be unwise to draw conclusions from aggregate global debt figures, and more useful to focus on particular pockets of indebtedness around the world.

Many economists are particularly concerned about the situation in China, where corporate bank-borrowing has exploded since the global financial crisis. Many suspect that much of that Chinese corporate borrowing has been wasted, risking a destabilising financial crisis or long-term sclerosis for the world’s second-largest economy.

The Bank of England is also keeping a close eye on UK credit card debt and car loans, for fear that many families could be making themselves vulnerable in the event of a new downturn.

Most economists also agree that it is undesirable that national tax systems effectively favour debt funding for firms over equity funding (shares and direct ownership stakes by investors) by making the former tax deductible.