|

The astika-mata or orthodox schools of Indian philosophy are six in number, Sāmkhya, Yoga, Vedanta, Mimamsa, Nyaya and Vaisesika, generally known as the six systems (saddarsana).

The nastika schools of Indian philosophy are three in number, Buddhist, Jaina and the Carvaka.

The later neither regard the Vedas as infallible, nor try to establish their own validity on their authority.

The belief that the world is full of sorrow, although common to all these systems, has not been equally emphasized in all of them; but finds its strongest utterance in Samkhya, Buddhism and Yoga. Yet, neither of these last philosophies are bittersweet; on the contrary, they teach you the path of a joyful deliverance.

Kapila कपिल ऋषि was a Vedic sage credited as one of the founders of the Sāṃkhya school of philosophy.

Samkhya is the first attempt to systematize the religious speculations of the Upanishads, the sacred texts of Hinduism of a mystical nature, that deal with metaphysical questions, and which take their roots in the Vedas.

Samkhya is also a strong reaction against the ritualistic practices of sacrifices.

Sāmkhya is a philosophy that is strongly atheist and dualist. Already in the Upanishads there are references to diverse atheistical creeds (Svetasvatara,) but not as digested as in Sāmkhya.

Sāmkhya philosophy regards the universe as consisting of two realities; Puruṣa (Self(ves)) and Prakriti(phenomenal realm of matter).

The Samkhya system espouses dualism by postulating two irreducible, innate and independent realities: Purusha and Prakriti. While the Prakriti is a single entity, the Samkhya admits a plurality of the Puruṣas in this world.

Proto-Samkhya thoughts are found in the Chandogya Upanishad, the Katha Upanishad, the Svetasvatara Upanishad (late) - in the Arthasastra of Kautilya - in the Moksadharma and Bhagavadgita (Mahabharata)

A simple account

An even simpler account

A more demanding account

___

A simple account

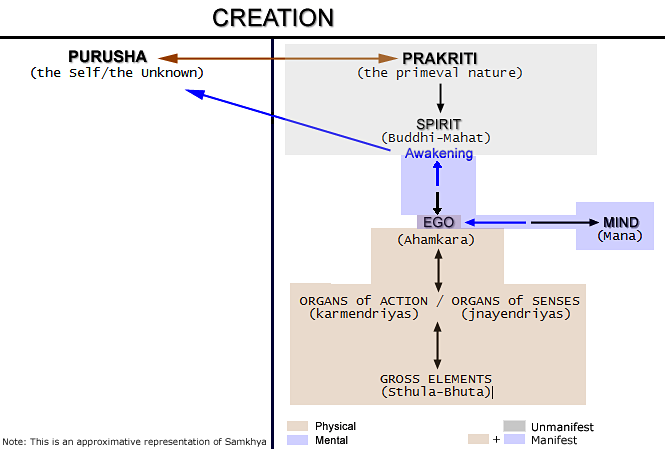

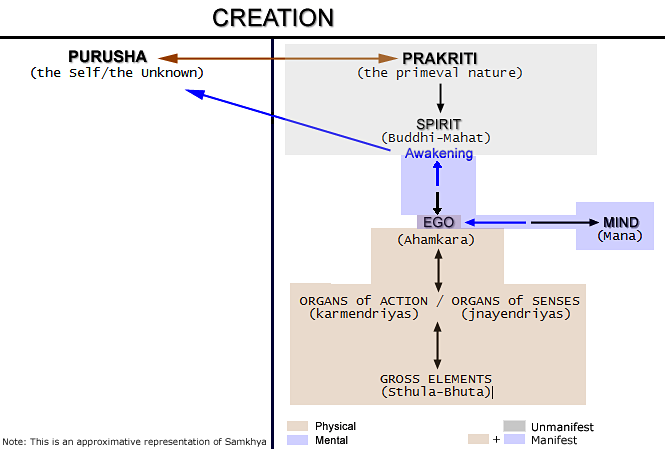

There are two entirely distinct principles at the origin of creation: Purusha (the Cosmic Being(s)) and Prakriti (Nature).

When these two distinct principles meet, there is creation.

Purusha the “controller” is intelligent, indifferent and inactive, yet pervasive; and when it meets Prakriti, it pervades both the conscious* and the unconscious things; it pervades both the evolvents (the internal organs such as the Spirit (Awakening) (Buddhi or Mahat;) the Ego (Ahamkara) and the Mind (Mana;) as well as the evolutes (the external organs of senses (karmendriyas) and organs of action (jnayendriyas); and as well as the gross elements (Stula-bhuta / aka sky, eath, water, fire, etc.)

Evolvent and evolute may be considered as “maker” and “made;” or "cause" and "effect".

Nothing exists before the two (Purusha and Prakriti) meet.

As a dancer starts dancing when the spectator looks at her; so Prakirti starts its activity and the production of first, the evolvents and then, the evolutes.

The levels of production are the following:

Buddhi (aka Mahat) is the first evolvent to be produced by the primeval Prakriti, at the contact of Purusha.

Buddhi is determination, in the sense that it fixes the properties of things.

Later on, once things are created and known through the Ego (Ahamkara) and the Mind (Mana), it will be that internal organ (Awakening) that discriminates between Prakriti and Purusha.

Ego (Ahamkara) is what makes beings (Linga, or the Subtle body). It drives the progressive creation of the individuality as character, as a person; both physically and mentally. Then later on, it will be “self-awareness” with the help of Aatmaa + Kshetrii (Soul - as knower of the body) and Mana (Mind).

Mana helps the Ego (Ahamkara) to know about the created things; both those created by the Ego itself, as well as all the other created things.

Mana is determinative. It has the power or quality of deciding. It is a cognitive power. It is both of the nature of the organ of Senses and the organs of Action.

Mana is the realm of Reflection and Meditation.

Path of Creation:

Prakriti -> Mahat -> EGO -> Organs of Action and Senses -> Gross Elements.

(Note: Up to here, this is very Kantian)

Path of Knowledge:

Gross Elements -> Organs of Action and Senses -> EGO & Mana -> Mahat -> Prakriti.

(Note: This is pretty Hegelian, up to Mahat, where Hegel considered Spirit (Mahat) as belonging both to Prakriti and Purusha).

In these two processes, the attributes, the qualities, the constituents of Prakriti known as GUNAS operate to gain an end; namely the liberation of Purushas.

The production of composite objects by these processes are meant for another; that is to say, for Purusha.

Purusha exists because these composite objects are meant for another, but also because there must be control, because there must be someone who enjoys and because there is activity for release.

The Gunas are the following:

- SATTVA (Delusion): It illuminates. It is bright and light.

- RAJA (Pleasure): It activates. It is active and mobile.

- TAMAS (Pain): It restrains. It is heavy and enveloping.

They mutually exists and consort, support and produce, or suppress.

They are the inception of bondage.

Prakriti, endowed with the attributes (gunas) without benefit to itself, causes by manifold means, the benefit of the Purusha; which is devoid of attributes and which confer no benefit in return.

The “non-intelligent” Prakriti is like the milk that nourishes the calf.

As a dancer desists from dancing after showing herself to the viewer, so Prakriti must desists after showing itself to Purusha.

"I AM NAUGHT; NAUGHT IS MINE - THERE IS NO EGO"

By this knowledge, Purusha, seated, composed like a spectator, perceives Prakriti which has ceased to be productive.

One, Prakriti, desists (“I have been seen”).

One, Purusha, desists (“I have seen”).

* Consciousness must be taken here in the sense of “awareness” or “non-awareness;” (discernment) and not in the sense of the Samkhyan’s mental state; in which thought is not involved.

_______

Samkhya - An even simpler account!

Raise your hands and open up your fingers!

Now call your left hand H - and your right hand 2O.

Keep the fingers streched-out, lower the hands at chest level, and in a horizontal movement join them; like if you were about to help someone climb a stone wall. Hold tight! That’s a hell of a grip; a mighty good bond, isn’t it?

Call that grip, that bond: H2O or water.

Call that grip, that bond: the gist of Samkhya.

For H is Purusha and 2O is Prakriti. And from them is the bond of creation.

Now, imagine yourself in the desert with no water. A drop of it would be a blessing; a good thing - a great quality of H2O.

Simultaneously, imagine yourself at the bottom of a mountain, with a cool little river flowing next to your house; and suddenly a great storm passes and your house is swept away by the flood. That would be a curse, a bad thing - an evil quality of H2O.

Does H or P have any of these qualities in themselves; but the binding?

This is Samkhya.

When the Samkhyan tries to reach either one of the primary elements, one of the distinct monads, he does not care if creation is the fact of a God (might He exist), or if it is ruled by a civilization that comes from the other end of the universe (might it be true); or, as a matter of fact, about anything that is mental and physical.

All he cares about is to unbound!

__________

A more demanding account

THE SAMKHYA SYSTEM

The Samkhya system represents a notable departure in thought from what may be called the formalistic habit of mind. By its emphasis on the principle of continuity, it marks, in some degree, the abandonment of the tendency to view the universe as tied up in neat parcels. Its rejection of the rigid categories of the Nyaya-Vaiseika as inadequate instruments for describing the complex and fluid universe, makes it a real advance on the theory of atomistic pluralism.

Neither, as in the metaphysico-religious concepts of the Upanishads, is the world an act of a creator God, who summoned up by a single fiat of his will a world entirely distinct from himself, but is the product of the interaction between the infinite number of spirits (Purushas) and the ever-active Prakriti, or the potentiality of nature

The Samkhya philosophy assumes the reality of Purushas and Prakriti from the fact of knowledge, with its distinction between the subject and the object. No explanation of experience is possible if we do not assume the reality of a knowing self and an object known.

In Kapila's doctrine, for the first time in the history of the world, the complete independence and freedom of the human mind, its full confidence in its own powers, were exhibited.

Samkhya is a notable attempt in the realm of pure philosophy.

Note: In the early texts, "Samkhya" is used in the sense of philosophical reflection and not numerical reckoning.

When the Samkhya claims to be a system based on the Upanishads, there is some justification for it, though the main tendency of the Upanishads is radically opposed to its dualism.

The first mention of the Samkhya is in the Svetasvatara Upanishad, though the elements coordinated into the system are to be met with in the earlier Upanishads.

Not only the notions of rebirth and the unsatisfactoriness of the world, but also such central principles as that knowledge is the means to release, and Purusha is the pure subject, are taken from the Upanishads.

In the Katha Upanishad, the unmanifested (avyakta) stands at the top of an evolution series on the plane of matter, from which the great self (mahan-atma,) intellect, mind, objects and senses spring in succession. Self-sense (ahamkara) is not mentioned and the supreme Spirit is admitted.

The first product of Prakriti is called mahat, the great one; and the natural source of this idea is the Upanishad conception that the supreme Spirit reappears as the first-born of creation, after producing primitive matter.

The classification of the psychical functions may have been suggested by the account of the Prasna Upanishad regarding the states of sleep, dream, etc.

The Svetasvatara Upanishad contains a more developed account of the Samkhya principles of the cosmos, the three gunas; though the Samkhya elements are subordinated to its main doctrine of theism. It identifies pradhana and maya as well as Brahman and Purusha .

By its insistence on the absolute reality and independence of Spirit, the Samkhya set itself against all materialist views of mental phenomena. We do not come across any stage of the development of the Samkhya at which it can be identified with materialism.

The relation of the Samkhya to early Buddhism has given rise to much speculation as to mutual borrowing. Though the Samkhya works, which have come down to us, are later than the origin of Buddhism, and may have been influenced by Buddhist theories, the Samkhya ideas themselves preceded Buddha, and it is impossible to regard Buddhism as the source of the Samkhya.

Insistence on suffering, the insubordination to Vedic sacrifices and denunciation of ascetic extravagances, indifference to theism and the belief in the constant becoming of the world (parinaminityatva) are common to Buddhism and the Samkhya.

These casual coincidences are not enough to justify the theory of mutual borrowing, especially in view of the marked divergences between the two. Buddhism did not accept any of the central principles of the Samkhya, an inactive Purusha, an ultimate Prakriti and the theory of the gunas . If the Buddhist chain of causation resembles, in some respects, the Samkhya theory of evolution, it is because both of them have for their common source the Upanishads.

In Asvaghosha's Buddhacarita (the first account on Samkhya in Buddhist litterature,) we have an account of a meeting between Buddha and his former teacher Arada, who holds the Samkhya views, though in a theistic setting. It seems to be very probable that the earliest form of the Samkhya was a sort of realistic theism, approaching the Visishtadvaita view of the Upanishads.

The Purusha is the subject of knowledge, the twenty-fifth principle set over against the other twenty-four principles of nature which are the objects of knowledge.

Final release is effected by a recognition of the fundamental distinction between spirit and nature.

The plurality of spirits is empirical. The souls are many - so long as they are in union with nature - but when they realise their distinction from it, they return to the twenty sixth principle of Purusha.

While this type of Samkhya may be regarded as a legitimate development of the teaching of the Upanishads, the dualistic Samkhya, which insists on the plurality of Purushas and the independence of Prakriti, and drops all account of the Absolute, can hardly be said to be in line with the teaching of the Upanishads. The question is, how did it happen that the Samkhya rejected the idea of the Absolute

The Samkhya did not become a well co-ordinated system until after the rise of Buddhism. When Buddhism offered a challenge to realism, the Samkhya accepted the challenge and argued on strictly rational grounds for the reality of selves and objects. When it developed on a purely rationalistic soil, it was obliged to concede that there was no proof for the existence of God.

Historically, though, it may be accepted that a historical individual of the name of Kapila was responsible for the Samkhya tendency of thought. We shall not be wrong if we place him in the century preceding Buddha.

The Samkhya Karika, of Isvarakrishna is the earliest available as well as the most popular textbook of the school.

Isvarakrishna in his Karika, describes himself as being in the succession of disciples from Kapila through Asuri and Pancasikha. Asuri probably lived before 600 B.C., if he be one with the Asuri of the Satapatha Brahmana.

From the few fragmentary passages that have come down to us, Pancasikha held the theory of the three gunas. He regarded the purushas as atomic in size, and attributed the connection of Purusha and Prakriti to want of discrimination rather than to works.

CAUSALITY

The theory that the effect really exists beforehand in its cause is one of the central features of the Samkhya system.

The Samkhya defines cause as the entity in which the effect subsists in a latent form, and gives the following grounds in support of it :

(1) The non-existent cannot be the object of any activity.

(2) The product is not different from the material of which it is composed.

(3) It exists before it comes into being in the shape of the material. If this is not admitted, then anything can come out of anything.

(4) Causal efficiency belongs to that which has the necessary potency.

(5) The effect is of the same nature as the cause.

PRAKRITI

From the principle of causality it is deduced that the ultimate basis of the empirical universe is the unmanifested (avyaktam) Prakriti. The Samkhya Karika argues for the existence of Prakriti on the following grounds:

(I) Individual things are limited in magnitude.

Whatever is limited is dependent on something more enduring and pervasive than itself. The finite as finite, therefore, cannot be the source of the universe.

(2) All individual things possess certain pervasive characteristics, thus implying a common source from which they all issue. The Samkhya does not believe that the different elements are completely distinct from one another.

(3) There is an active principle manifesting itself in the development of things. Evolution implies a principle which cannot be equated with anyone of its stages. It is something larger than its products, though immanent in them.

(4) The effect differs from the cause, and we cannot, therefore, say that the finite and conditioned world is its own cause.

(5) There is the obvious unity of the universe, suggesting a single cause.

While every effect is caused, Prakriti has no cause, but is the cause of all effects, from which it is inferred.

The products are caused, while Prakriti is uncaused; the products are dependent, while Prakriti is independent; the products are many in number, limited in space and time, while Prakriti is one, all-pervading and eternal. The products are the signs from which we infer the source.

Prakriti can never perish, and so it could never have been created. An intelligent principle cannot be the material out of which the inanimate world is formed, for spirit cannot be transfomled into matter. Besides, agency belongs not to the Purusha or the soul, but to the ahamkara or self-sense, which is itself a product.

The difficulty that Prakriti is not perceived is not of much moment. There are ever so many things which are accepted as real, though they are not open to perception. Perception cannot succeed with regard to objects too near or too remote.

Defects of senses or manas, obstruction of another object, or presence of more attractive stimuli, render perception useless.

The fineness of Prakriti renders it imperceptible.

Prakriti is that which never is nor is not, that which exists and does not exist, that in which there is no non existence, the unmanifested, without any specific mark, the central background of all.

Again, nothing that exists can be destroyed, and the products exist in Prakriti, though in an unmanifested state. In it all determinate existence is implicit. The different gunas do not annul themselves, but are in a state of equipoise, which is not inactivity but a kind of tension. Prakriti is not so much being as force. As the equilibrium of the three gunas, it is the ground of all modifications, physical and psychical.

It is pure potentiality.

We do not know the real nature of Prakriti or the gunas, since our knowledge is confined to phenomena. It is devoid of sound and touch, practically the limit beyond which we cannot go. It is empirically an abstraction, a mere name. But it must be assumed to exist as the prius of all creation.

The Samkhya description of the world in terms of one homogeneous substance, of which all things are but different configurations resulting from the different combinations of its ultimate constituents, has some resemblance to the materialist theory.

Both of them assert the ultimate reality of a primary substance which they regard as eternal, indestructible and ubiquitous. The multiplicity of heterogeneous things which we come across in our ordinary experience is traced to this single substance.

They admit, while the materialists do not, that the evolution of Prakriti is purposive.

The Prakriti of the Samkhya is not a material substance, nor is it a conscious entity, since Purusha is carefully distinguished from it.

It gives rise not only to the five elements of the material universe, but also to the psychical. It is the basis of all objective existence.

The real in its fulness is distinguished into the unchanging subject, and the changing object, and Prakriti is the basis of the latter, the world of becoming. It is the symbol of the never-resting, active world stress. It goes on acting unconsciously, without regard to any thought-out plan, working for ends which it does not understand.

THE GUNAS

The development of Prakriti arises by means of its three constituent powers, or gunas, which are postulated in view of the character of the effects of Prakriti. Prakriti is a string of three strands. Buddhi, which is an effect, has the properties of pleasure, pain and bewilderment, and so its cause, Prakriti, must have answering properties. The gunas are not perceived, but are inferred from their effects.

- The first of these is called sattva. I t is said to be buoyant or light.

- The second, rajas, is the source of all activity and produces pain. Rajas leads to a life of feverish enjoyment and restless effort.

- The third is tamas, that which resists activity and produces the state of apathy or indifference.

The respective functions of sattva, rajas and tamas are manifestations (prakasa), activity (pravritti), and restraint (niyamana), producing pleasure, pain and sloth.

The tendencies to manifestation (sattva) and activity (rajas) are held in check by the tendency to non-manifestation and non-activity (tamas).

The three gunas are never separate. They support one another and intermingle with one another. They are closely related as the flame, the oil and the wick of a lamp. They constitute the very substance of Prakriti. All things are composed of the three gunas, and the differences of the world are traced to the predominance of the different gunas.

They are called gunas (or qualities,) since Prakriti alone is substantive, and these are merely elements in it. They may be regarded as representing the different stages of the evolution of any particular product. The sattva signifies the essence or the form which is to be realised, the tamas the obstacles to its realisation, and the rajas represents the force by which the obstacles are overcome and the essential fonn is manifested.

A thing is always produced, never created, according to the Samkhya theory of Satkaryavada. Production is manifestation and destruction is non-manifestation. These two depend on the absence and presence of counteracting forces.

Since these moments are found in all existence, they are attributed to the original Prakriti.

Note: In the early Upanishads they stand for psychic states which produce physical and mental evil.

The gunas are said to be extremely fine in texture. They are always changing. Even in what is regarded as the state of equilibrium the gunas are continually changing into one another. These changes in themselves do not produce objective results, so long as the equilibrium is undisturbed. If there is a disturbance of the equilibrium (gunakshobha,) then the gunas act on one another and evolution takes place.

They are devoid of the power of discriminating between themselves and Purusha . They are always objective, while Purusha alone is subject.

When there is a disturbance of the equilibrium of the gunas, we have the destruction of Prakriti, the relieving of the tension by the overweighting of one side, and the letting in of the process of becoming. Prakriti evolves under the influence of purusha. The fulfilment of the ends of the purusha is the cause of the manifestation of Prakriti in the three specialised states.

The cause of development follows a definite law of succession in space, time, mode and causality. We cannot say why this development happens. We have only to accept it. Prakriti, which contains within itself the possibilities of all things, develops into the apparatus of thought as well as the objects of thought.

Mahat, or the Great, the cause of the whole universe, is the first product of the evolution of Prakriti.

It is the basis of the intelligence of the individual. While the term mahat brings out the cosmic aspect, buddhi, which is used as a synonym for it, refers to the psychological counterpart appertaining to each individual.

From the synonyms of buddhi, and its attributes of virtue (dharma), knowledge (jñana), equanimity (vairagya), and lordship (aisvarya), and their opposites, it is clear that buddhi is to be taken in the psychological sense.

Buddhi is not to be confused with the incorporeal Purusha.

It is the faculty by which we first determinate (posit) then distinguish objects and perceive what they are.

The memories are stored in buddhi, and not in ahamkara or manas.

Buddhi, as the product of Prakriti and the generator of ahamkara, is different from buddhi which controls the processes of the senses, mind and ahamkara.

Ahamkara (self-sense), or the principle of individuation, rises after buddhi. Through its action the different spirits become endowed each with a separate mental and physical background.

Ahamkara is conceived as material, and while buddhi is more cognitive in function, ahamkara seems to be more practical. Psychologically, the function of ahamkara is abhimana or self-love. Agency belongs to it, and not to the self or Purusha.

MANAS

Mana is said to be the doorkeeper, while the senses are regarded as the doors! The co-operation of manas is necessary for both perception and action.

It assumes manifold forms in connection with different senses. Manas is not all pervading, since it is an instrument possessing movement and action. Mana is determinative. It has the power or quality of deciding. It is a cognitive power. It is both of the nature of the organ of Senses and the organs of Action.

The five organs of perception are the functions of sight, hearing, smell, taste and touch. The need creates the function. Since we have the desire, we create the functions and the objects to satisfy them. The senses are not eternal, since their rise and lapse are seen. Each sense grasps one quality.

They are the means of observing the fine and the gross elements.

The organs of action are the functions of the tongue, feet, hands, and the organs of evacuation and reproduction.

The world as the object of perception has the five tanmatras, corresponding to the five sense-organs. These are the essences of sound, touch, colour, taste and smell conceived as physical principles, imperceptible to ordinary beings. Each of them is exclusively concerned with one sense, while the gross elements appeal to more than one sense. These invisible essences are inferred from visible objects, though they are said to be open to the perception of the yogis.

Akasa forms the transition link between ahamkara, and the tanmatras. A distinction is made between karanakasa, non-atomic and all-pervasive, and karyakaSa, or atomic akaSa, formed by the combination of ahamkara, or mass, units with the sound essences.

The series from Prakriti to the five gross elements numbers twenty-four, and Purusha is said to be the twenty- fifth principle of the Samkhya system.

Evolvent & Evolutes (Cause and effect)

- Mahat, ahamkara, and the five tanmatras are the effects of some and causes of others.

- The five gross elements and the eleven organs are only effects and not causes of others.

- While Prakriti is only cause,

- the eleven products are simply effects.

- Seven of the products are both causes and effects,

- while the Purusha is neither cause nor effect.

The different principles of the Samkhya system cannot be logically deduced from Prakriti, and they seem to be set down as its products, thanks to historical accidents. There is no deductive development of the products from the one Prakriti.

Buddhi, ahamkara, manas and the rest need not be taken as a series of chronologically successive stages of evolution. They are the results of the logical analysis of evolved selves.

While the nature of the supreme is cognizant, that of Prakriti is uncognizant; and when the two intermingle we have awareness-unwareness, or subject-object, and that is mahat (Buddhi).

Immediately the subject contrasts itself with the object, it develops the sense of selfhood (Ego). There is first intelligence and then selfhood. Creation is preceded by a sense of selfhood.

SPACE AND TIME

Every phenomenon of cosmic evolution is characterised by activity, change or motion (parispanda).

All things undergo infinitesimal changes of growth and decay. In the smallest instant of time (kshana) the whole universe undergoes a change.

In the empirical world, space and time appear as limited, and are said to arise from akasa, when it is conditioned by coexistent things in space and moving bodies in time. The world has phenomenal reality as undergoing transformations.

Cosmic process is twofold in character, creative as well as destructive. Creation is the unfolding of the different orders from the original Prakriti, and destruction is the dissolution of them into the original Prakriti.

As a result of the disturbance of the condition of equilibrium, the universe is evolved with its different elements, and at the close of the world-period the products return by a reverse movement into the preceding stage of development, and so finally into Prakriti.

Prakriti remains in this condition until the time arrives for the development of a new universe. This cycle of evolution and reabsorption has never had a beginning and will never have an end.

The play of Prakriti does not cease when this or that individual attains release, though the emancipated are unaffected by the action of Prakriti.

To the souls in bondage it evolves into many a form from the subtlest to the grossest; and to the freed it retraces its steps and becomes resolved into its own primeval form. So long as there are spectators, the play of Prakriti goes on. When all souls are set free, the play is over and the actors retire.

But as there will be always souls struggling to escape out of entanglement in Prakriti, the continuous rhythm of Prakriti's activity will be maintained for ever.

Samsara will never reach its end.

Since the state of dissolution is the normal condition, in the state of evolution there is a tendency to lapse into dissolution. When the desires of all Purushas require that there should be a temporary cessation of all experience, Prakriti returns to its quiescent state. The gunas are so finely opposed that no one becomes predominant.

There is therefore no generation of new things and qualities.

PURUSHA

All organic beings have a principle of self-determination, to which the name of "soul" is generally given.

The different souls in Samkhya, are fundamentally identical in nature. The differences are due to the physical organisations that obscure and thwart the life of the soul.

Idem, the nature of the bodies in which the souls are incorporated accounts for their various degrees of obscuration.

The Samkhya asserts the existence of Purusha freed from all the accidents of finite life and lifted above time and change.

There is the testimony of consciousness that, though the individual is in one aspect a particular finite being subject to all the accidents and changes of mortality, there is something in him which lifts him above them all. He is not the mind, life or body, but the informing and sustaining soul, silent, peaceful, eternal, that possesses them.

When the facts of the world are viewed from the epistemological point of view, we get a classification into subjects on the one side and objects on the other. The relation between any subject and any object is that of cognition or, more broadly, experience. The Samkhya regards the knower as Purusha and the known as Prakriti.

The Samkhya puts forward several arguments to establish the existence of Purusha:

(1) The aggregate of things must exist for the sake of another.

there is a self for whose enjoyment this enjoyable body, consisting of intellect and the rest, has been produced."

(2) All knowable objects have the three gunas, and they presuppose a self who is their seer devoid of the gunas.

(3) There must be a presiding power, a pure consciousness which co-ordinates all experiences.

(4) Since Prakriti is non-intelligent, there must be someone to experience the products of Prakriti.

(5) There is the striving for liberation (kaivalya), which implies the existence of a Purusha with qualities opposed to those of Prakriti.

The consolidation of our experiences into a systematic whole is due to the presence of the self, which holds the different conscious states together.

The self is defined as different from the body, or Prakriti (manifest and unmanifest).

Purusha's nature as unfailing light (sadaprakasasvarupa) does not change. It is present in dreamless sleep, as well as in states of waking and dreaming, which are all the modifications of buddhi.

Purusha exists, though it is neither cause nor effects.

Prakriti and its products are not self-manifested, but depend for their manifestation on the light of Purusha.

Purusha is not bliss, for happiness is due to the sattva guna, which belongs to the side of Prakriti.

Pleasure and pain belong to the buddhi.

Pura is incapable of movement, and on attaining release it does not go anywhere.

It is not of limited size, since then it would be made up of parts and so be destructible.

It does not participate in any activity. The Samkhya denies the Purusha all qualities, since otherwise it would not be capable of emancipation.

There are many selves,

There are many conscious beings in the world, each regarding the world in his own way, and with an independent experience of its subjective and objective processes.

If the self were one, all should become free if anyone attained freedom.

If the self is opposed in nature to Prakriti, which is one and common to all, the plurality of selves follows.

Freedom is not coalescence with an absolute spirit, but isolation from Prakriti.

The Samkhya view of Purusha is determined by the conception of Atman in the Upanishads. It is without beginning or end, without any qualities, subtle and omnipresent, an eternal seer, beyond the senses, beyond the mind, beyond the sweep of intellect, beyond the range of time, space and causality, it does not know all things in the empirical sense, for empirical cognition is possible only through the limitations of body.

Purusha is unrelated to Prakriti. Purusha is said to be outside Prakriti, and its influence on Prakriti, though real, is unintelligible. It is mere witness, a solitary, indifferent, passive spectator. The evolution of Prakriti implies spiritual agency. But the spiritual centres admitted by the Samkhya are incapable of exerting any direct influence on Prakriti; the Samkhya says that the mere presence of the Purushas excites Prakriti to activity and development. It is Prakriti alone that reacts to the proximity of Purusha; like a dancer, aware of the presence of the spectator, starts dancing for him.

Prakriti is active and ever-revolving, while Purusha is inactive (akarta). Purusha is unalterably constant, while Prakriti is so alterably. Prakriti is characterised by the three gunas , while Purusha is devoid of the gunas;

If Prakriti were spontaneously active, then there can be no liberation, since its activity will be unceasing; if it were spontaneously inactive, then the course of mundane existence would at once cease to go on. The Samkhya admits that the activity of Prakriti implies a mover not itself in motion, though it produces movement.

The collective influence of the innumerable selves which contemplate the movement of Prakriti is responsible for the evolution of the latter. The disturbance of the equilibrium of the gunas which sets up the process of evolutio is due to the action of the Purusha s on Prakriti.

The presence of the Purushas disturbs the balance of the forces which keep each other at rest.

The efficient cause of Prakriti's development is not the mere presence of the purushas, for they are always present, but their non-discrimination.

To say that the activity of Prakriti is for the benefit of Purusha is a figurative way of saying that it is for the purification of buddhi.

The Samkhya assumes not only the proximity of the Purusha to buddhi, but also the reflection of Purusha in buddhi.

Note: The Purusha of the Samkhya is not unlike the God of Aristotle. Aristotle affirmed a transcendant God as the origin of the motion of the world, and denied to his God, (like the Samkhya with Purusha,) any activity within the world.

*

|